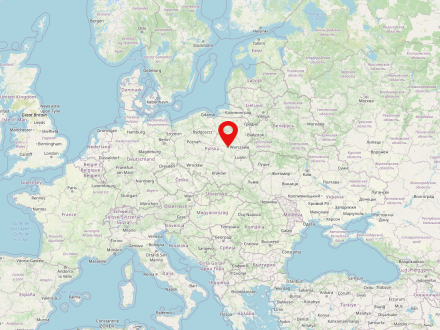

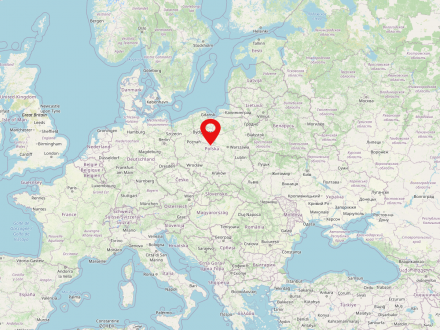

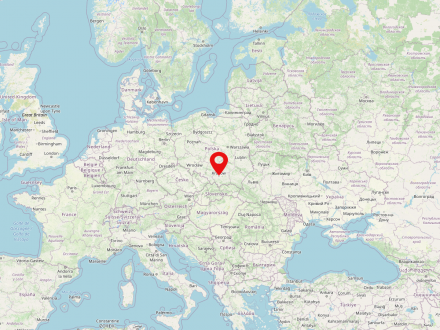

Warsaw is the capital of Poland and also the largest city in the country (population in 2022: 1,861,975). It is located in the Mazovian Voivodeship on Poland's longest river, the Vistula. Warsaw first became the capital of the Polish-Lithuanian noble republic at the end of the 16th century, replacing Krakow, which had previously been the Polish capital. During the partitions of Poland-Lithuania, Warsaw was occupied several times and finally became part of the Prussian province of South Prussia for eleven years. From 1807 to 1815 the city was the capital of the Duchy of Warsaw, a short-lived Napoleonic satellite state; in the annexation of the Kingdom of Poland under Russian suzerainty (the so-called Congress Poland). It was not until the establishment of the Second Polish Republic after the end of World War I that Warsaw was again the capital of an independent Polish state.

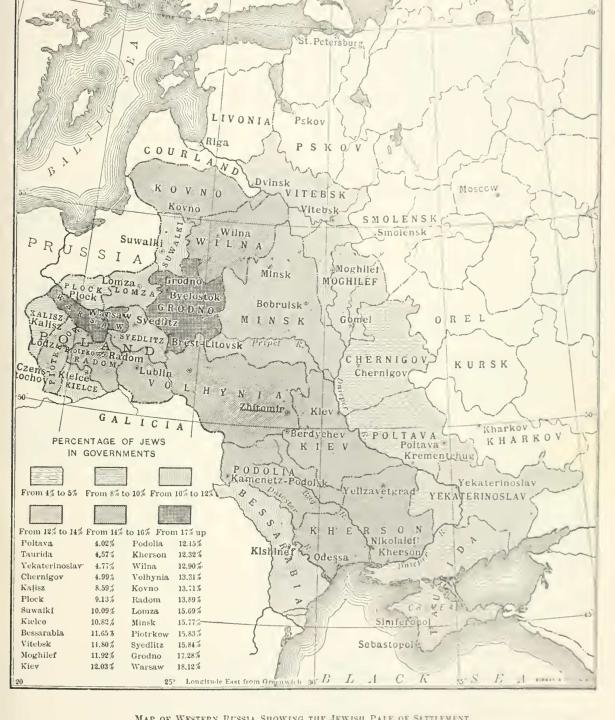

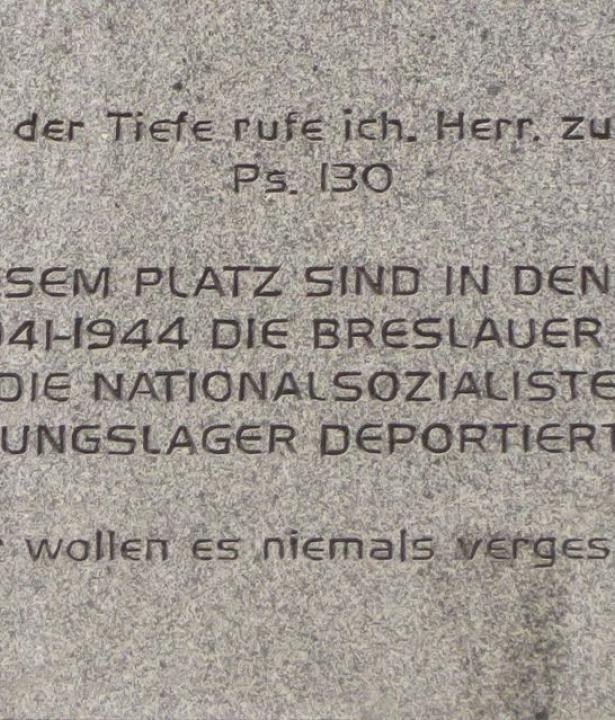

At the beginning of World War II, Warsaw was conquered and occupied by the Wehrmacht only after intense fighting and a siege lasting several weeks. Even then, a five-digit number of inhabitants were killed and parts of the city, known not least for its numerous baroque palaces and parks, were already severely damaged. In the course of the subsequent oppression, persecution and murder of the Polish and Jewish population, by far the largest Jewish ghetto under German occupation was established in the form of the Warsaw Ghetto, which served as a collection camp for several hundred thousand people from the city, the surrounding area and even occupied foreign countries, and was also the starting point for deportation to labor and extermination camps.

As a result of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising from April 18, 1943 and its suppression in early May 1943, the ghetto area was systematically destroyed and its last inhabitants deported and murdered. This was followed in the summer of 1944 by the Warsaw Uprising against the German occupation, which lasted two months and resulted in the deaths of almost two hundred thousand Poles, and after its suppression the rest of Warsaw was also systematically destroyed by German units.

In the post-war period, many historic buildings and downtown areas, including the Warsaw Royal Castle and the Old Town, were rebuilt - a process that continues to this day.

Poland is a state in Central Eastern Europe and is home to approximately 38 million people. The country is the sixth largest member state of the European Union. The capital and biggest city of Poland is Warsaw. Poland is made up of 16 voivodships. The largest river in the country is the Vistula (Polish: Wisła).

Irena Krzywicka cited in Agata Tuszyńska: Krzywicka. Długie życie gorszycielki, Kraków 2011, 31–34. English translation by the author

I had a very long life … I lived through all possible misfortunes, not the Holocaust itself, but I lost almost all those I loved. They say about me that I was a star. A star of the salons. I was considered to be pretty; I led an interesting and colourful life. I had wonderful, devoted friends that I loved dearly. Antoni Słonimski was one of them, then, Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz … Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński played a huge role in my life. He was my maitre a penser, my teacher and guide. What was amusing, and actually paradoxical, was that I used to know almost the entire Polish school of mathematics … I knew so many people in my life… I knew not only Polish writers, but also many French literati … I knew Pope John XXIII … After the war … I lost nearly all my relatives; I was walking on graves. I thought I was not going to survive it, that I would not be able to live on…But I’m still alive, damn it, and I keep on living and I keep on living.

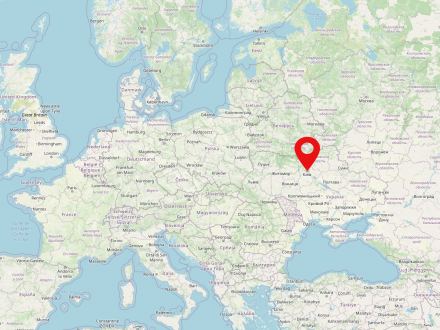

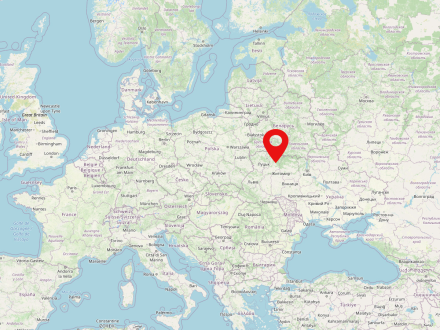

Kiev is located on the Dnieper River and has been the capital of Ukraine since 1991. According to the oldest Russian chronicle, the Nestor Chronicle, Kiev was first mentioned in 862. It was the main settlement of Kievan Rus' until 1362, when it fell to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, becoming part of the Polish-Lithuanian noble republic in 1569. In 1667, after the uprising under Cossack leader Bogdan Chmel'nyc'kyj and the ensuing Polish-Russian War, Kiev became part of Russia. In 1917 Kiev became the capital of the Ukrainian People's Republic, in 1918 of the Ukrainian National Republic, and in 1934 of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Kiev was also called the "Mother of all Russian Cities", "Jerusalem of the East", "Capital of the Golden Domes" and "Heart of Ukraine".

Kiev is heavily contested in the Russian-Ukrainian war.

Due to the war in Ukraine, it is possible that this information is no longer up to date.

Lviv (German: Lemberg, Ukrainian: Львів, Polish: Lwów) is a city in western Ukraine in the oblast of the same name. With nearly 730,000 inhabitants (2015), Lviv is one of the largest cities in Ukraine. The city was part of Poland and Austria-Hungary for a long time.

Due to the war in Ukraine, it is possible that this information is no longer up to date.

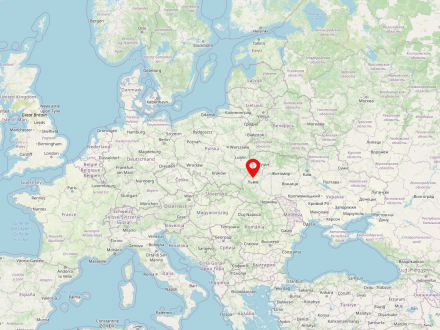

Krakow is the second largest city in Poland and is located in the Lesser Poland Voivodeship in the south of the country. The city on the Vistula River is home to approximately 775,000 people. The city is well known for the Main Market Square with the Cloth Halls and the Wawel castle, which form part of Krakow's Old Town, a UNESO World Heritage Site since 1978. Krakow is home to the oldest university in Poland, the Jagiellonian University.

Zuzanna Ginczanka: Non omnis moriar, in: Michał M. Borwicz (ed.), Pieśń ujdzie cało... Antologia wierszy o Żydach pod okupacją niemiecką (Centralna Żydowska Komisja, 1947). English translation from: http://www.70voices.org.uk/content/day50

„Non omnis moriar“

Non omnis moriar — my proud estate,

Table linen fields, staunch wardrobe fortresses,

Acres of sheets, precious linens

And dresses, bright dresses will survive me.

As I leave no heir,

Let your hands rummage through Jewish things

Chomin, woman of Lwów, brave wife of a spy,

Swift informant, Volksdeutscher’s mother.

May they be useful to you and yours, not some strangers.

“My dear ones” — it’s no song, nor empty name.

I remember you as you, when the Schupo came,

Remembered me. Reminded them of me.

So let my friends sit with goblets raised

To celebrate my memory and their own wealth,

Rugs and tapestries, candlesticks, bowls –

Let them drink all night, and at dawn,

Let them begin to search for gemstones and gold

In sofas, mattresses, quilts and rugs.

Oh, how they’ll make quick work of it,

lumps of horsehair and sea grass stuffing,

Clouds of torn pillows and eiderdown quilts

Will coat their hands and turn their arms to wings;

My blood will tie these fibres with fresh down,

And transform these winged ones to angels.

Berezne is a city (population 2022: 13,126) in the northwest of Ukraine. It is located in the historical landscape of Volhynia. Before the Second World War, it was the place with the highest proportion of Jews in Poland at the time (94.6%).

In G. Bigil (ed.) Mayn shtetele Berezne, Tel Aviv: Berezner Society in Israel: 1984, p. 161. Translated from Hebrew by Yechiel Weizman.

When the partisan fighters were merged with the liberating Russian army in November 1944, we were discharged from the partisans and sent to Kiev. With the liberation of Berezne we passed through several towns in Volhynia. We arrived in our Berezne, and our eyes could not grasp what we saw – the town was forlorn and empty of Jews. The destruction was horrible and indescribable, the Jewish houses were deserted and destroyed and those which remained intact were occupied by strangers. It’s impossible to recognize this town, that only five years earlier flourished. We didn’t ask where the Jews were – our fathers, brothers, sisters. We, around forty Jews, who were wondering around the ruins of the widowed town, knew that their bones are buried in the pits, in big holes. Yet, we were afraid to go there alone, it was not before a governmental committee of Jews and Russians came to inspect the graves that we went to the graves of our fathers and children. We found a levelled piece of land, without any trace of a mound. We removed the surface of the ground and revealed a grave packed with male corpses. The bodies were placed one on top of the other in layers and between the bodies there was plaster, and around, next to the edges of the graves, there were bodies sitting. In the second grave women were buried, almost in the same position, and, in the third grave, we found children’s skeletons. Our parents and dear relatives, whose life was brutally taken by the evil men, our heart exploded from this terrible and frightening sight. At the end of the inspection, we reconstructed the graves with our own hands, placed some soil around them and erected a tziun [monument], without knowing whether it would be preserved. We stood broken around the graves and shed tears. After saying the Kaddish, we left the place. The story of Berezne had ended.

The Soviet Union (SU or USSR, Russian: Союз Советских Социалистических Республик (СССР) was a state in Eastern Europe, Central and Northern Asia existing from 1922 to 1991. The USSR was inhabited by about 290 million people and formed the largest territorial state in the world, with about 22.5 million square km. The Soviet Union was a socialist soviet republic with a one-party system.

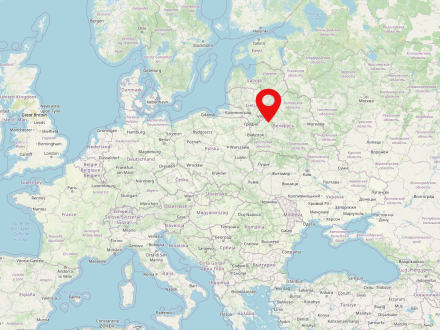

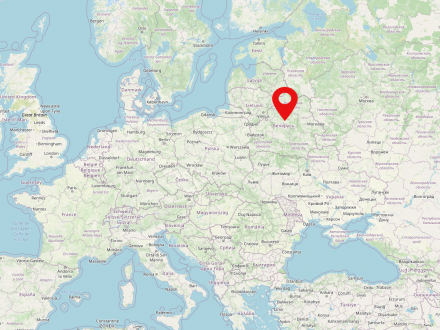

Iwie is a town (population in 2022: 7,243) and a former shtetl in the west of Belarus. The town was first mentioned in 1444. Iwie is considered the town with the highest proportion of Tatar population in the country. The town was also historically characterized by the coexistence of different ethnicities and religions.

Belarus is a state in eastern Europe inhabited by about 9.5 million people. The capital and most populous city of the country is Minsk. After the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991, the state is independent. Belarus borders Ukraine, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia and Russia.

Tamara Baradach, born in 1949. The interview was collected during the research project “Mapping the Archipelagos of Lost Towns” by Ina Sorkina, 08.07.2020 and 21.12.2020. The research was funded by the Gerda Henkel Foundation. English translation by the author.

For us, children, the days of May 11th-12th were a holiday that we would always look forward to …. This was the day when all those who survived came to Iŭje. And they would talk, and I could hear this language, which I didn’t understand, Yiddish … All these survivors would come to our place … For us it was a day of a family visit, because we had no families. Polish children would go to church, Tatar children into a mosque, and we wouldn’t go anywhere, only to the cultural center at the former synagogue. And we celebrated no holidays. We only had this one day of sorrow and sadness, but also joy – because our family would come to visit …. My mom and dad would call all those survivors “boys”, “our boys”. And when we were growing up, we always thought that they were our uncles. And we addressed them as such. We thought these were our father’s brothers, and these were actually the survivors of Iŭje. And when they addressed my mom, they would call her Aunt Nyura, even though she was the same age as they were. They just wanted to call her “auntie” because they had no families: no aunts, no uncles, no parents. They were all buried in one pit.

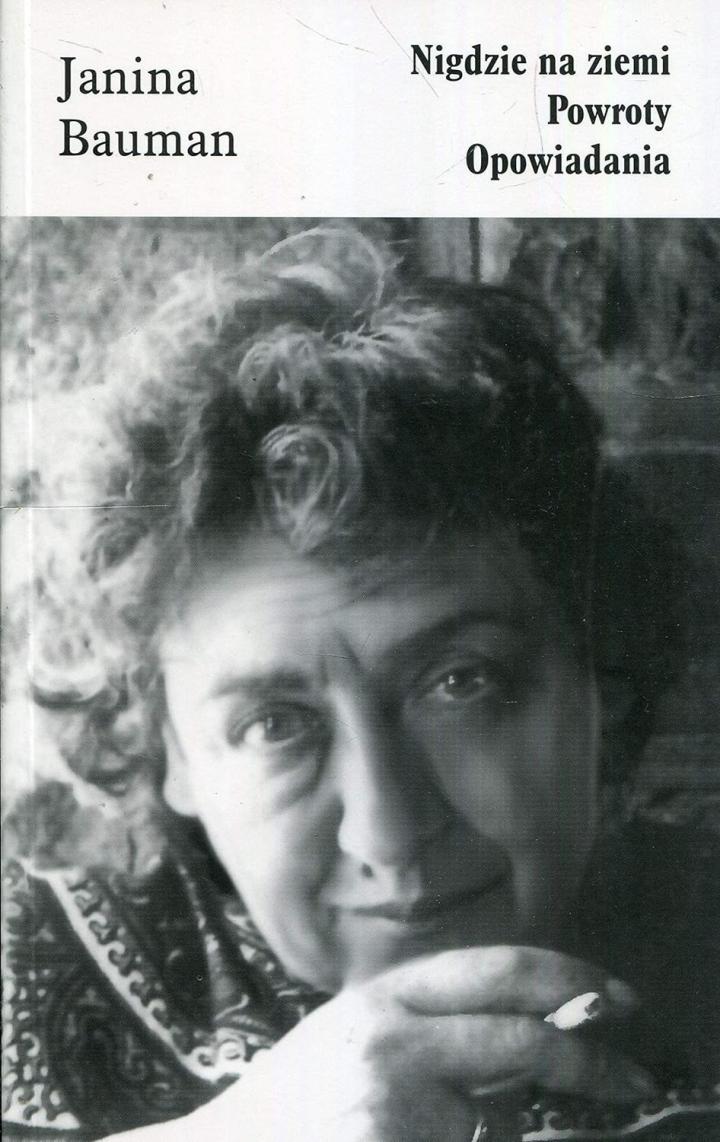

Janina Bauman, Nigdzie na ziemi: Powroty: Opowiadania, Łódź: Wydawnictwo Officyna, 2011, pp. 147-156. English translation by the author.

The last day of January 1968 began a caesura in my life and that of my family, even though we did not realize it back then yet. That day, the censors decided to cancel the theatre performance of Adam Mickiewicz’s Forefathers’ Eve at the National Theatre. This provoked stormy protests of students and intellectuals ... Students … were demanding the freedom of expression, and protested against censorship and state security organs, they also condemned the racism of the official propaganda that was blaming the protests principally on Jewish students. On March 19th, in the evening, there was a meeting of Władysław Gomułka with the Party activists. The TV was broadcasting it live … finally, they got to the point that the public seemed to have been waiting for since the beginning of the meeting. ‘Last year, during the Israeli aggression against the Arab states, a number of Jews demonstrated the will to leave for Israel and join the war against the Arabs. There is no doubt that this category of Jews, Poland’s citizens, is not emotionally and rationally bound with Poland, but with Israel. To those who consider Israel to be their homeland, we are ready to issue emigration passports.’ A buzz went through the hall. … Applause, feet stamping and exclamations: “Down with the Zionists” and … “Your end is near, pack your suitcases” drowned the rest of the speech. The atmosphere at the Congress Hall started smelling of a pogrom. Fear overwhelmed us. In a minute, the meeting will come to an end, and the Party activists will go drinking, the mob will exit the streets of Warsaw to deal with the Zionists, with a full blessing of the Party. … We fell into a panic. ... My daughters gathered all the heavy and sharp objects we possessed—a huge ashtray, the only sharp knife, a wooden head of an African warrior in a spiked helmet and a few sturdy cooking pots. The view of this arsenal amused us, although there was actually nothing to laugh about.

Katka Reszke, Return of the Jew: Identity Narratives of the Third Post-Holocaust Generation of Jews in Poland, Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2019, pp. 18-20.

When I was about sixteen years old, I started “becoming Jewish.” I read everything I could find in Polish and in English about Jews and Judaism, and I talked about Jews and about Judaism at home and in school. My high school friends started calling me a Jew. … I discovered a number of odd rituals and customs my great-grandma used to practice. Nobody knew what they meant, and it was not until I studied Judaism that I could actually decipher the meaning behind them. Without going into details, some of the “strange” things my great-grandmother used to do were keep her milk and meat dishes separate and follow strict rules when baking challah bread, including the laws of hafrashat challah—removing a piece of the dough from the batch, and covering the two challah loaves with a cloth. She had only one elusive answer to any questions her children or grandchildren asked about the obscure rules: “It’s just a custom.” She knew the customs from her mother—my great-great-grandmother—and in fact we suspect today that perhaps it was my great-great-grandmother who made sure that the family’s Jewishness would eventually be successfully obscured. She could not have known that a few generations later I would come along and mess with her plan. After all, Great-Grandma had a point when she used to call me meshuggeneh, which means “crazy” in Yiddish…. In my early twenties, I ended up immigrating to Israel, where I lived for almost five years… As a largely secular person today, I continue to bewilder many Jews and non-Jews alike with the fact that I continue to perform many Jewish rituals, that I shake the “four species” on the Jewish holiday of sukkot, that I make kiddush over wine, or that I refuse to work on shabbat. My grandmother as well as my parents turned out to be fully sympathetic to my decision to pursue a Jewish affiliation, and to my amazement and pride, my parents chose to declare double nationality—Polish and Jewish—in the recent Polish national census.