Jewish history in this exciting century reflects these phenomena and sharpens our sense of the depth of change, as the Jewish community had long seen itself primarily as a religious group without this question even being asked. As the period of secularization continued, religious affiliation became more fragile, and was often replaced by cultural or linguistic concepts of belonging and the associated feelings of community and imagination based on a sense of national identity. This also happened within the Jewish communities, but these affiliations never took the place of religion „automatically“ or „without any alternative“, partly due to the diaspora situation; instead, they were always controversial, both within the Jewish communities and in dialog with other communities, where resistance to the Jewish search for affiliation arose. Parallel to the traditionally religiously motivated hatred of Jews, which is often referred to as anti-Judaism

Galicia is a historical landscape, which today is almost entirely located on the territory of Poland and Ukraine. The part in southeastern Poland is usually referred to as Western Galicia, and the part in western Ukraine as Eastern Galicia. Before 1772, Galicia belonged for centuries to the Polish-Lithuanian noble republic, and subsequently and until 1918 - as part of the crown land "Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria" - to the Habsburg Empire.

For this reason, „marriage certificates“ were introduced, with which young people wishing to marry had to prove that they had a school-leaving certificate, as well as the ability to speak German. While many Jewish subjects took advantage of the various modernization measures, others resisted the pressures that resulted from them. Jewish family networks and, above all, religious communities were transnational and trans-imperial, and the new borders played no binding role in the reality of the lives of believers who made pilgrimages to the court of a tsaddik, for example. In order to regulate these practices, the state tried to control internal Jewish migration with the help of a passport system and to expel so-called „beggar Jews“.

In addition to these coercive measures, economic conditions and the urbanization typical of the 19th century were all reasons for migration to the Hungarian parts of the empire, to the big cities, especially Vienna, to Western Europe, and the USA. Jews in Austria were emancipated in 1867.

The Kingdom of Prussia existed from 1701 to 1918 and was reigned by the Hohenzollern dynasty. The country was an absolute monarchy from its founding until 1848 and a constitutional monarchy from 1848 until its dissolution. The capital of the Kingdom of Prussia was Berlin. The land was inhabited by about 40 million people. After the November Revolution of 1918 and the abdication of Wilhelm II, the Kingdom dissolved and formed the Free State of Prussia.

From 1812, Jews in Prussia and other German territories were granted equal legal status. Many of the migrants quickly shed their Eastern European roots and, only a generation later, their communities were already starting to view immigrants from Eastern Europe skeptically and considering them „backward“. From the end of the 19th century, in addition to the alienation from Eastern European Jews, there was also a nostalgic glorification of the Eastern European Jewish past, a longing for the supposedly „authentic“ Jewish life in the shtetl.

Jewish migration contributed greatly to the rapid growth of cities in the 19th century; in Berlin, the Jewish population rose from 6,400 at the beginning to 150,000 at the end of the century.

Before the partitions of Poland, there had hardly been any Jewish subjects in the

The Russian Empire (also Russian Empire or Empire of Russia) was a state that existed from 1721 to 1917 in Eastern Europe, Central Asia and North America. The country was the largest contiguous empire in modern history in the mid-19th century. It was dissolved after the February Revolution in 1917. The state was regarded as autocratically ruled and was inhabited by about 181 million people.

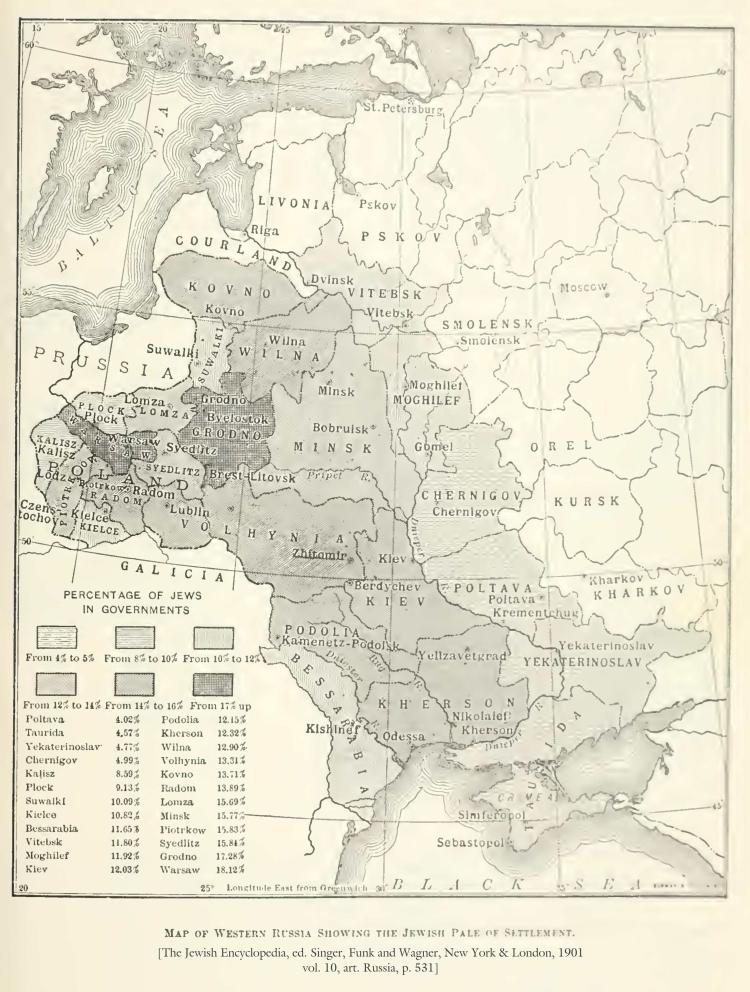

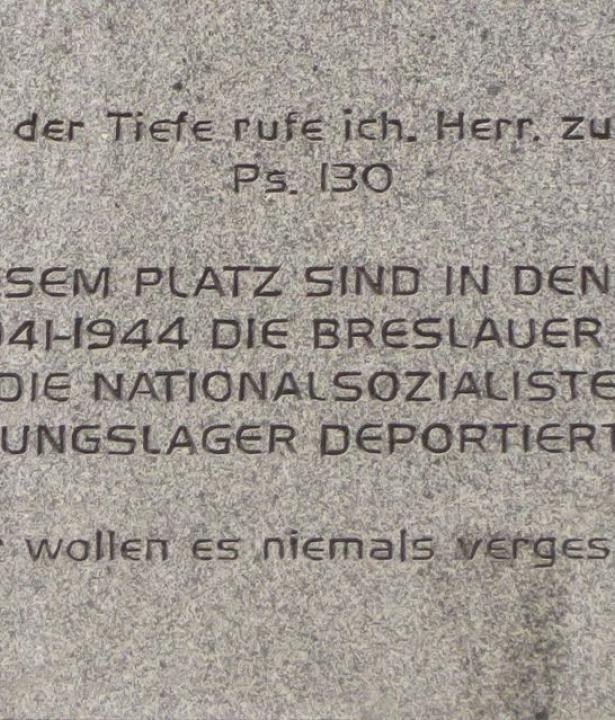

Apart from a few exceptions, Jews in the Russian Empire did not enjoy the right to live outside the settlement area, which had settlement restrictions until 1915. These exceptions were Jews perceived as „useful“ by the authorities, including academics, wealthy merchants, sought-after craftsmen, and those who had completed many years of military service. A small, influential Jewish upper class was recruited from this group, whose members often attempted to act as advocates, in the traditional sense, (shtadtlonim), for the interests of the entire Jewish population in the Russian Empire.7 Until the abolition of serfdom in 1861, and due to a specific passport system, the vast majority of subjects of the Russian Empire did not enjoy freedom of movement. The Jewish population was therefore no exception. However, this situation changed for many people in the Russian Empire during the second half of the 19th century. Only for the Jewish population did the restriction to the settlement area remain, and it even intensified, especially from 1881 onwards. As a result, over time the settlement area was increasingly perceived as a metaphor for the all-encompassing discrimination against the Jewish population in the Russian Empire and was fought against as such. Numerous influential Jewish intellectuals and politicians, such as the famous historian and Jewish national ideologist Simon Dubnow (1840-1941), were forced to live illegally in the metropolises of the Russian Empire under humiliating circumstances.8 The fate of a possible expulsion always hovered over the heads of the people who had left the settlement area. In 1891, for example, the Jewish population was expelled from Moscow.

Another important result was the Jewish political search for community. Parallel to emigration, the first circles of the Chibbat Zion (Love of Zion) movement emerged in the Russian Empire, which can be considered an early form of the Zionist movement. Non-Zionist Jewish political community projects also emerged. Jewish socialism and diaspora nationalism were particularly important.