We are constantly faced with new treks. One meets acquaintances, and everywhere there is the same suffering, the same worry, the anxious uncertainty and also indifference. People are almost at the end of their strength!1

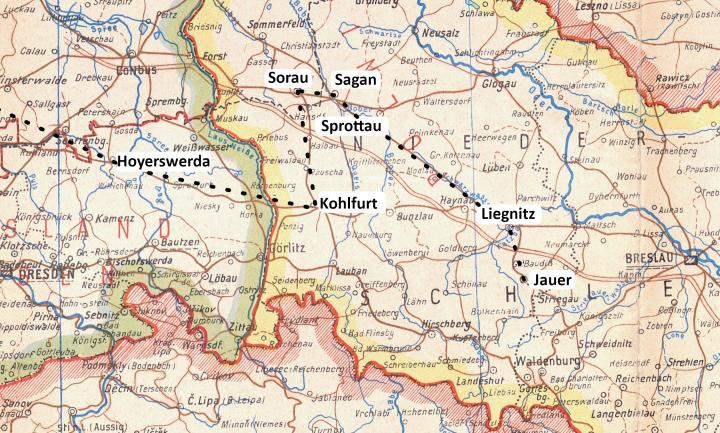

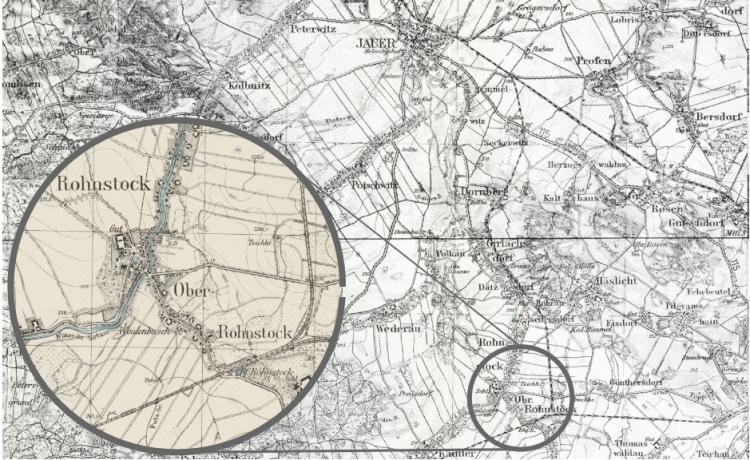

The Lower Silesian town of Jawor is located on the River Nysa Szalona, about 70 km west of Wroclaw, in present-day Poland, and was first documented in written records in the 11th century. Jauer was a center of the Reformation. An important trading center in the 14th century, the town later became known for linen weaving and letterpress printing, and other industries became established from the 19th century.

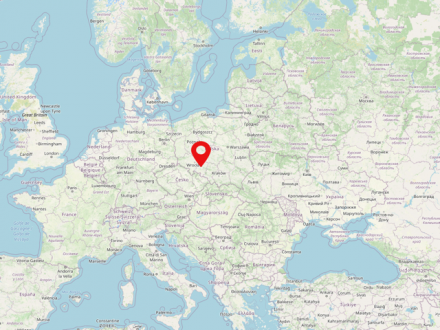

Silesia (Polish: Śląsk, Czech: Slezsko) is a historical landscape, which today is mainly located in the extreme southwest of Poland, but in parts also on the territory of Germany and the Czech Republic. By far the most significant river is the Oder. To the south, Silesia is bordered mainly by the Sudeten and Beskid mountain ranges. Today, almost 8 million people live in Silesia. The largest cities in the region are Wrocław, Opole and Katowice. Before 1945, most of the region was part of Prussia for two hundred years, and before the Silesian Wars (from 1740) it was part of the Habsburg Empire for almost as many years. Silesia is classified into Upper and Lower Silesia.

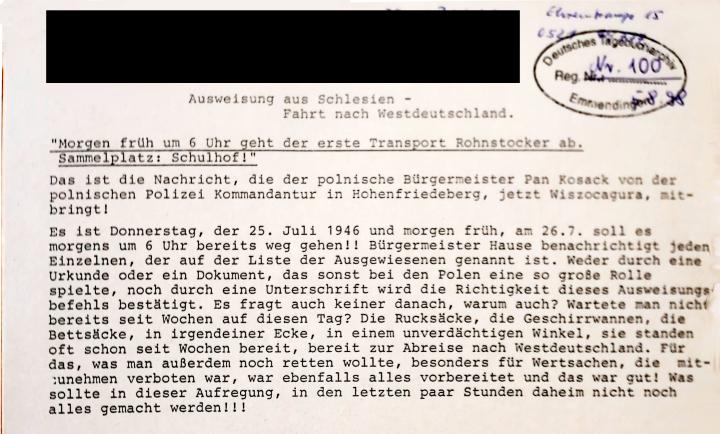

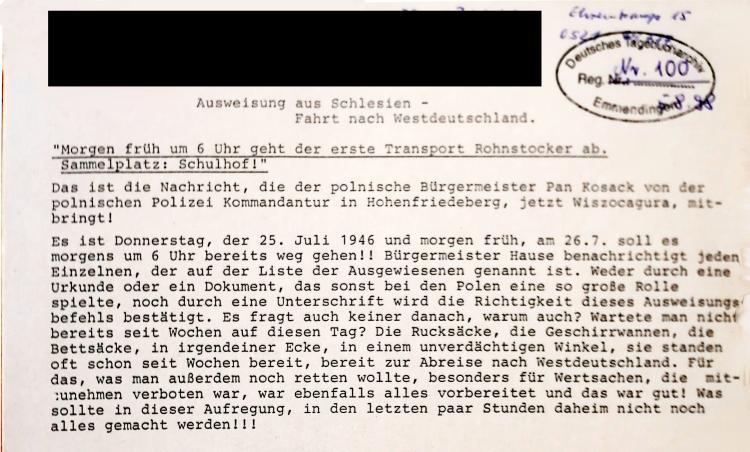

Hadn't they been waiting for this day for weeks? With backpacks, dish tubs, bed sacks stowed there in some unsuspicious corner, many people had been ready for weeks, ready to leave for West Germany. Arrangements had also been made for the safekeeping of other things – things one wanted to save, especially valuables that we weren’t allowed to take with us – and that was good!2

Legnica is a city inhabited by 99,000 people in the Polish voivodeship of Lower Silesia. The city is located in the west of the country not far from the capital of the voivodeship, Wroclaw. Legnica was part of the Prussian province of Silesia till 1945.

The Lower Silesian town of Szprotawa is located in Poland today and has about 11,500 inhabitants. It was first mentioned in the year 1000. Particularly in the first half of the 20th century, the economy of Szprotawa flourished due to the success of local industries.

Żary is located in the Polish part of Lower Lusatia and, with just under 40,000 inhabitants, is the second largest city in Lower Lusatia after Cottbus. In 1007 the area "Zara" was mentioned in writing for the first time. In 1260 Sorau was granted city rights. Together with Lower Lusatia, Sorau became part of the Electorate of Saxony in 1635 and Prussia in 1815. In the 19th century it became a center of the textile industry, which flourished in the region.

Żary is located in the Polish part of Lower Lusatia and, with just under 40,000 inhabitants, is the second largest city in Lower Lusatia after Cottbus. In 1007 the area "Zara" was mentioned in writing for the first time. In 1260 Sorau was granted city rights. Together with Lower Lusatia, Sorau became part of the Electorate of Saxony in 1635 and Prussia in 1815. In the 19th century it became a center of the textile industry, which flourished in the region.

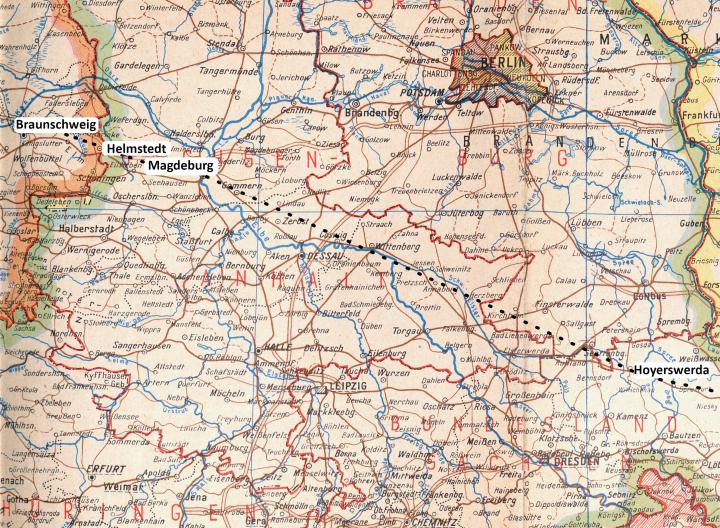

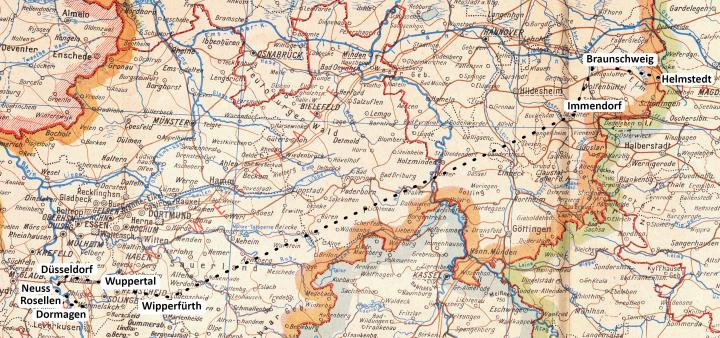

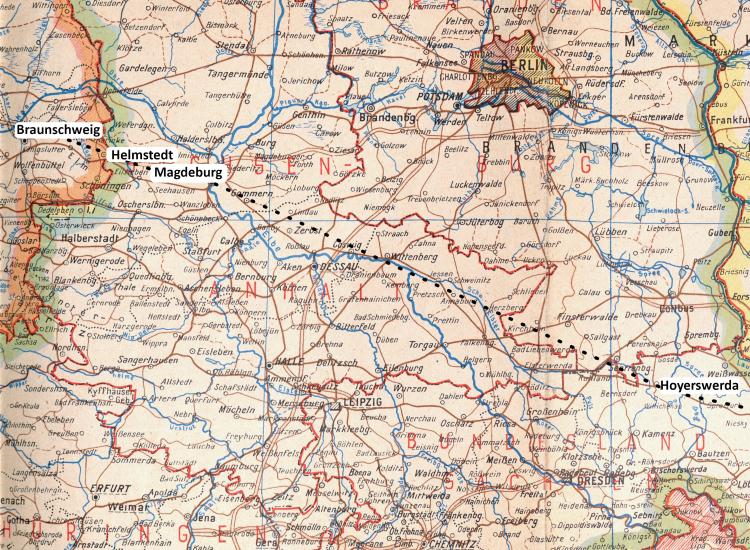

We [...] continued our journey refreshed! We travelled via Hoyerswerda in the direction of Magdeburg. There, for the first time, we saw the destruction of the war. On both sides of the railway line stood burned-out housing blocks [...].7

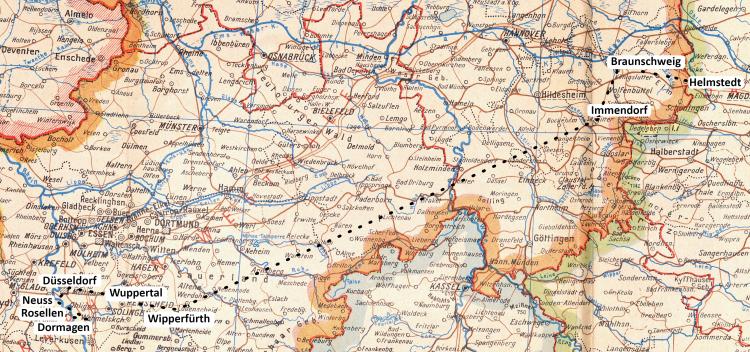

Hilda spends several days at the Immendorf camp and a kind of normality returns, even though questions about the future are always present.

It is the 6th of August. We are still in the Immendorf camp. When will we move on? Are we now going to our final destination or first to a camp again? Are we going to be powdered again for vermin? These are the little questions about our future that occupy us at the moment.10

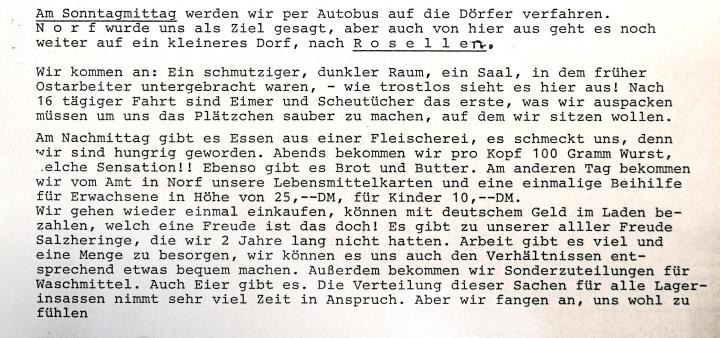

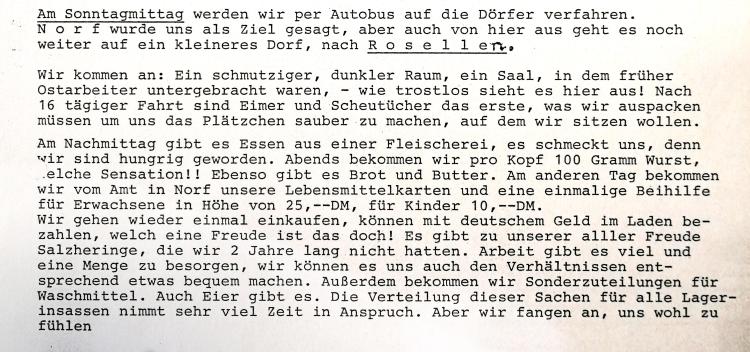

On Sunday at noon we were transported by bus to the villages. We were told Norf was our destination, but from here we continued on to a smaller village, Rosellen.12

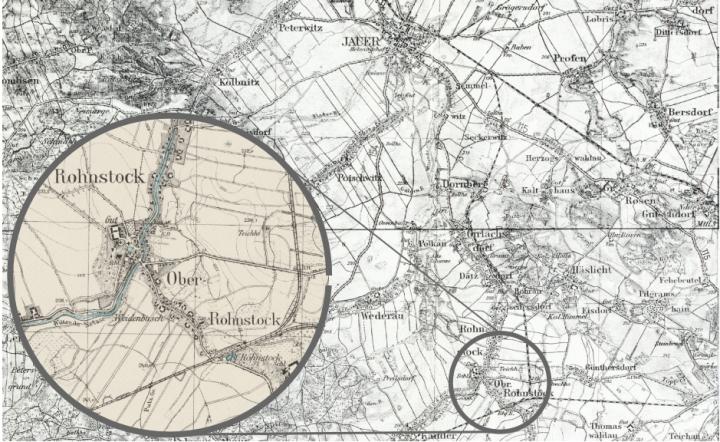

Map material from the map collection of the Herder Institute

English translation: William Connor

Cartographic montages: Laura Gockert

Editing: Christian Lotz