Some disdain it as an enclave of a consumerist, unthinking middle class. Others sing its praises and consider it a one-of-a-kind urban development project. No other urban district in Poland has been written about and discussed as much as the Miasteczko Wilanów. But where do the roots of this discussion lie? What part do literature and other art forms play in the reproduction of those narratives? And what does the reality behind the stereotypes and urbanistic homages actually look like?

Text

If you follow Warsaw's Royal Route, one of the Polish capital's oldest and most important traffic arteries, southward from the city center, it is only a matter of 30 minutes by bus before you leave the proliferation of 1980s row houses and brand-new gated communities of Sobieskiego Street, which connects downtown and southern Warsaw. Five-story building complexes now appear in front of you, in the midst of which a monumental building stands out like a raised index finger: the Temple of Divine Providence – a place of worship that was conceived of as far back as 1791 but was not constructed until 200 years later. The history and timeline of the surrounding residential area is rather more straightforward. Planned in 1998, construction began four years later, in 2002,1 and continues to this day. Only the official name of the district, Błonia Wilanowskie, stands as a reminder that this was previously a marshland – that and the huge number of mosquitoes in late summer. But hardly anyone calls this district by that name. Nowadays, another, much better-known name prevails: Miasteczko Wilanów.

Miasteczko Wilanów is situated on a former marshland. The administrative name Błonia Wilanowskie is a reminder of this. Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

Miasteczko Wilanów is situated on a former marshland. The administrative name Błonia Wilanowskie is a reminder of this. Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

One of the Miasteczko’s main intersections: Klimczaka Street links the Temple of Divine Providence with the Royal Castle of Wilanów, while Rzeczypospolitej Street divides the suburb in a north-south direction. Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

One of the Miasteczko’s main intersections: Klimczaka Street links the Temple of Divine Providence with the Royal Castle of Wilanów, while Rzeczypospolitej Street divides the suburb in a north-south direction. Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

The idea of a mini city within the city

Text

This label did not come about simply by chance. It comes from the original building concept for the area, which was developed in 1998 by the main investors of the project Prokom and INVI Investments.2 The plan was to create a small town within the city, a miasteczko,3 which would combine residential and business areas as well as services and education facilities, all within walking distance of each other. It was to be a residential district, but very different from the gated communities that had become so popular in Warsaw in the 1990s in that it would have a high proportion of communal areas and attract a heterogeneous population. The idea was to establish a town where everyone would be able to enjoy the privileges and rights of living in a city and be able to exercise these within an active neighborhood culture.4 These ideas led to the project becoming a showcase of the New Urbanism architectural movement that was forming at the time of Miasteczko Wilanów's conception.

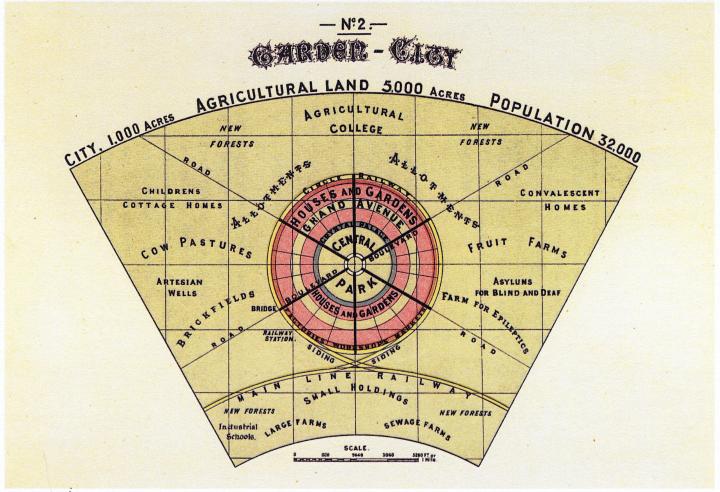

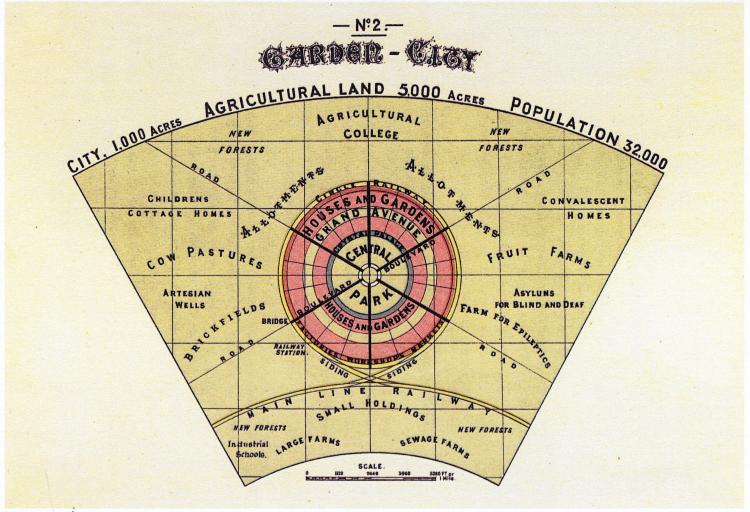

The concept of the Garden City by Ebenezer Howard (Diagram No 2). Howard, Ebenezer, To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform, London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co., Ltd., 1898., Free access - no reuse

The concept of the Garden City by Ebenezer Howard (Diagram No 2). Howard, Ebenezer, To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform, London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co., Ltd., 1898., Free access - no reuse

Text

The idea of Ebenezer Howard's Garden City was chosen as another conceptual pillar for the building project.5 Like Howard's Garden City, the Miasteczko was to house a maximum of 30,000 people from different social classes. In addition, it was to be dominated by public green spaces and efficiently connected to other parts of the city. A number of recreational facilities were also incorporated into the design, including a pond that could be used as a paddling pool in summer and an ice rink in winter, and a large park between the Miasteczko and the former Royal Castle in Wilanów. There was also to be a marketplace, a reminiscent nod to the area's original rural traditions.6 The master plan developed by the contractors stipulated that the buildings not exceed a certain height and follow a predetermined color scheme.7 These ambitious plans earned the project high-profile acclaim and awards in the field of urban design, including the "Excellence Award" from the international planners' association ISOCARP and the "Global Award of Excellence" from the Urban Land Institute.

If you take a stroll through the Miasteczko Wilanów today, apart from the occasional water features, the height of the buildings will probably stand out as the most eye-catching feature of the master plan. No building here has more than five stories and the uppermost level is always set back a little, which breaks up the visual axes. Until recently,8 the color scheme was also kept uniform throughout the district, creating an aesthetic homogeneity that is strengthened by the fact that even the exteriors of commercial establishments adhere to these same standards. One exception is the aforementioned church. The Temple of Divine Providence (Świątynia Opatrzności Bożej), as the church is officially called, was planned and built completely independently of the rest of the construction project. It was originally intended that the green areas surrounding the church be transformed into a park in keeping with the green and open concept of the Miasteczko. However, the construction fence that still surrounds the church is a clear sign that the grand vision of urban integration has not yet been fully realized.

Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

Text

A residential complex on Teodorowicza Street.

Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

Text

A view of Teodorowicza Street from Rzeczypospolitej Street.

Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

Text

A view of the (enclosed) courtyard of a residential complex on Ledóchowskiej Street.

Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

Text

A view of Hlonda Street.

Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

Text

A view of Rzeczypospolitej Street with water feature.

Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

Text

Residential complex on Kieślowskiego Street.

Text

However, numerous urbanistic studies also show that only a fraction of the ideas included in the original building concept ever came to fruition.1 For example, in 2021, there were almost 42,000 people living in the Miasteczko, which far exceeds the originally planned number of inhabitants. The idea that green spaces would account for two-thirds of the total area has also not been realized, resulting in far fewer recreational facilities, parks and public spaces. Thus, the project has drifted further and further away from the original idea of the Garden City.

Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

Text

One of the few green space projects to have been realized is the planted strip alongside the canal on Klimczaka Street, which features a path for pedestrians and joggers as well as children’s play areas.

Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

Text

Playgrounds are rare, but they do exist – mostly on the edges of the Miasteczko, like the large play area shown here “on the Orlik” in Worobczuka Street.

Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

Text

A community garden project in Worobczuka Street at the edge of the Miasteczko adds a touch of the garden city.

Text

Instead, gated communities have cropped up here, which contradict the original idea that was imagined (and sold) – that people would be able to walk freely through the streets and green spaces of the neighborhood. Large numbers of cars parked on the sidewalks represent a further obstacle, a result of there being too few parking spaces in the town plan. The parking situation becomes particularly critical when religious celebrations take place at the Temple of Divine Providence. At these times, road closures and pilgrim tourism cause the already scarce space to become even more limited.

A side street in Miasteczko Wilanów. Being a private street, the general parking ban does not apply here. Streets like this one are used as overflow parking spaces, both by residents and people who work in the Miasteczko. Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

A side street in Miasteczko Wilanów. Being a private street, the general parking ban does not apply here. Streets like this one are used as overflow parking spaces, both by residents and people who work in the Miasteczko. Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

There are also gates in the Miasteczko. Pictured is one of the many locked residential complexes. Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

There are also gates in the Miasteczko. Pictured is one of the many locked residential complexes. Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

Text

Contrary to the original vision, a private park was even established in the Miasteczko Wilanów – the first of the 21st century, which is only accessible to residents of the apartment complex it belongs to.9 The envisaged fusion of working and living also remains far from the reality we see in the district today. Only a few office spaces are available, and most people commute to work by car or bus to downtown Warsaw.

Many blame the private-sector organization of the construction project for the deviations from the original concept. The project was planned, designed and implemented by private construction companies rather than by the city of Warsaw. These in turn checked compliance with the aspects laid down in the master plan when reselling building plots. However, since the master plan was more of a guideline and the legally binding development plan approved by the city was general, projects were also approved that did not, for example, comply with the proportion of green space specified at the outset.10

From utopian building project to social and cultural imagination

Text

Due to the size of the undertaking, what was actually a private construction project soon became relevant at an urban policy level. Shortly after the completion of the first residential blocks, the new residents began demanding better educational facilities and transportation infrastructure. Private investors had not provided for such infrastructure, and the municipal authorities had not considered it. At the same time, the influx of a young, educated, high-income middle class into the district provoked public criticism, Increasingly, there were claims that this was the formation of an elitist politically and socially homogeneous enclave.

A key moment in the public discourse about the Miasteczko was the 2010 presidential election, in which 80% of the inhabitants of the Miasteczko Wilanów voted for the candidate of the liberal Platforma Obywatelska (PO) Bronisław Komorowski. This remarkable quota resulted in heated discussions in the Polish media about which social class a party would now have to win over in order to ensure success in the elections. (Left)-liberal media postulated that in the future the young metropolitan middle class would be decisive for the election and that national-conservative movements would thus be marginalized.11 Right-wing populist media then began to demonize these same young urbanites as politically unreflective followers. On both sides of the debate, the residents of Miasteczko Wilanów evolved into representatives of this population group.

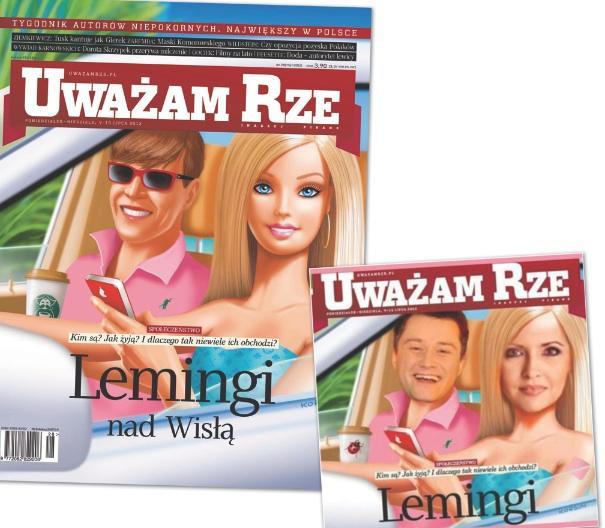

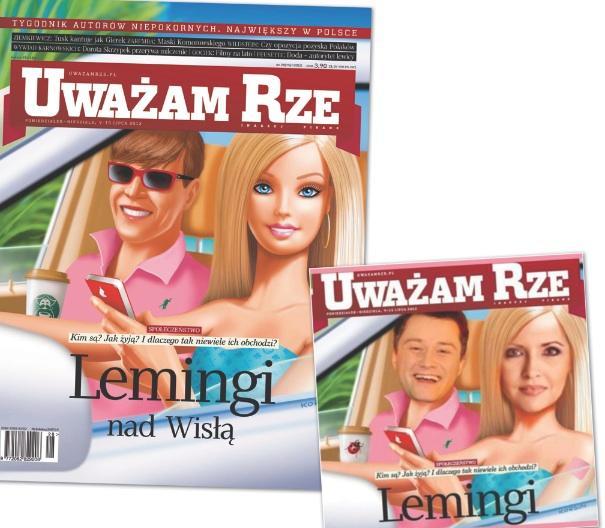

Cover of the weekly magazine Uważam Rze on the topic Lemingi z Wisły (Issue 9-15 July 2012). http://www.old.uwazamrze.pl/artykul/913095/zdrowie-nasze-w-gardla-wasze, Free access - no reuse

Cover of the weekly magazine Uważam Rze on the topic Lemingi z Wisły (Issue 9-15 July 2012). http://www.old.uwazamrze.pl/artykul/913095/zdrowie-nasze-w-gardla-wasze, Free access - no reuse

Text

The right-wing magazine Uważam Rze even called the inhabitants of Miasteczko lemmings, implying that they behave like herd animals, uncritically following political slogans of liberal parties and the media. They were portrayed as yes-men living in exclusive new housing estates – people who worked in international corporations earning lavish salaries, which they in turn wasted on senseless consumption.12 The Miasteczko itself now became Lemingrad – an allusion to the fact, during the years of the People’s Republic of Poland, the communist leadership had their residences in the old part of the Warsaw district of Wilanów, which was right next door.13 The decisive factor for this allusion was, on the one hand, the geographical proximity of the two residential areas to one another, and on the other hand, the supposed formation of an elite enclave. Right-wing populist media also came up with analogies linking the political opportunism of the inhabitants of the two neighborhoods. Like the communist elites in the 'old' Wilanów, the residents of Miasteczko became sociopolitical turncoats who unthinkingly followed the slogans of a certain political party – in this case the PO.

Based on this journalistic discourse, a similarly stereotypical image of the district emerged in the context of popular culture. In literary texts and theater productions, the inhabitants of the Miasteczko were and still are stylized as a homogeneous, wealthy, consumerist caste isolated from the rest of society and the city. This is most aptly demonstrated by the portrayal of the Wilanów middle class in the improvisational theater play Żony Wilanowa by Warsaw's Klub Komediowy. Based on popular series and films such as Desperate Housewives and Stepford Wives, the cabaret show depicts the lives of rich but bored women who live off their (ex-)husbands' money and whose daily routine consists of a repetitive sequence of beauty treatments, Pilates and shopping sprees.

Żony Wilanowa - trailer

The cover of Klaudia Klara’s book Poradnik Szczęśliwej Singielki (2017). https://lubimyczytac.pl/, Free access - no reuse

The cover of Klaudia Klara’s book Poradnik Szczęśliwej Singielki (2017). https://lubimyczytac.pl/, Free access - no reuse

Text

The vlogger Klaudia Klara describes the residents of Miasteczko as less bored but similarly affluent in her book Poradnik Szczęśliwej Singielki (2017).

In her portrayal, the district is inhabited by so-called "Korpoludki,"14 young, ambitious employees of international corporations, marketing sector workaholics. The character of "Excel-Anka" (82) is paradigmatic for this social class. After Excel-Anka moves from the center of Warsaw to Miasteczko, the narrator rarely sees her friend, and when she does, it is for a single drink. The drive home is too far, Excel-Anka says: "Ja nie mogę długo zostać. - Excel-Anka zawsze tak mówi. [...] - Powrót do Miasteczka Wilanów zajmie Bóg wie ile, a muszę jeszcze popracować w nocy [...]".15 The homogeneous and self-contained resident profile of the neighborhood becomes even more apparent in Klara's text when it turns out that this same Excel-Anka meets her dream man at a work training event, but it turns out that he also happens to live in the Miasteczko.

In her portrayal, the district is inhabited by so-called "Korpoludki,"14 young, ambitious employees of international corporations, marketing sector workaholics. The character of "Excel-Anka" (82) is paradigmatic for this social class. After Excel-Anka moves from the center of Warsaw to Miasteczko, the narrator rarely sees her friend, and when she does, it is for a single drink. The drive home is too far, Excel-Anka says: "Ja nie mogę długo zostać. - Excel-Anka zawsze tak mówi. [...] - Powrót do Miasteczka Wilanów zajmie Bóg wie ile, a muszę jeszcze popracować w nocy [...]".15 The homogeneous and self-contained resident profile of the neighborhood becomes even more apparent in Klara's text when it turns out that this same Excel-Anka meets her dream man at a work training event, but it turns out that he also happens to live in the Miasteczko.

Klara's popular literary text and the improv cabaret Żony Wilanowa thus reinforce the idea of the Miasteczko as an enclave of a rich, professionally successful, homogeneous middle class. Unlike the right-wing populist narratives about Lemingrad and its native lemingi, however, they do not classify the Miasteczko's inhabitants in sociopolitical terms.

Grzegorz Kalinowski's satirical novel Generacja X, czyli Kryzys Wieku Średniego (2021) and the Polish music journalist and producer Jan Chojnacki's autobiography Blues z kapustą (2016) take a different approach.

Text

One of the protagonists in Kalinowski’s novel Miasteczko Wilanów lives in an apartment that fell to her after her divorce from her husband. Here, too, the Miasteczko is described as a place where a new Warsaw middle class has found its “El Dorado:” “Kierownicy, menedżerowie, właściciele małych i średnich firm, pracownicy nieodległego TVN-u, czyli ogólnie rzecz biorąc: wszyscy, którym się udało […]. Młoda, prężna i wciąż rosnąca grupa, którą reszta warszawiaków nazywa korpoludkami lub lemingami, a ich dzielnicę – Lemingradem”.16 However, the narrator also adds his own commentary regarding those disrespectful labels. He points out very clearly that many statements are made out of envy and ill will: “Dla jednych brzmiało to pretensjonalnie – ci wypowiadali nazwę warszawskiej dzielnicy z przekąsem. Ci nieliczni, którzy mieszkali lepiej, nie mieli takich obiekcji, ale przeważali zazdrośnicy, którzy chętnie sami by się tam przeprowadzili”.17

Cover of Grzegorz Kalinowski’s Generacja X, czyli Kryzys Wieku Średniego (2021). https://lubimyczytac.pl/, Free access - no reuse

Cover of Grzegorz Kalinowski’s Generacja X, czyli Kryzys Wieku Średniego (2021). https://lubimyczytac.pl/, Free access - no reuse

The cover of Jan Chojnacki’s Blues z kapustą (2016),. https://lubimyczytac.pl/, Free access - no reuse

The cover of Jan Chojnacki’s Blues z kapustą (2016),. https://lubimyczytac.pl/, Free access - no reuse

Text

Chojnacki's account is somewhat less reflective. He cites the term lemmings, introduced by right-wing populist media, without discussing the origin of this phrase: "Tam gdzie dziś jest ostoja lemingów, czyli Miasteczko Wilanów, rozciągały się aż po Ursynów pola i nieużytki. Nieopodal miejsca, w którym straszy świątynia Opatrzności, było wysypisko śmieci, a w nim wielki dół zwany kopciówą".18 Nevertheless, there are parallels between Chojnacki's and Kalinowski’s portrayals of Miasteczko. Like Chojnacki, who looks back nostalgically to the former naturalness of the area and its peripheral character, thus evoking a kind of original spaciousness now lost to ongoing urbanization, Kalinowski also associates the district in his novel with a kind of colonization. Thus, he describes the inhabitants of Miasteczko, who come from all over Poland, as invaders who would conquer the Polish capital "jak Cortés w Ameryce".19

Text

In Rekin z parku Yoyogi (2014), the renowned Polish writer Joanna Bator also takes a pot shot at the Miasteczko. She, too, invokes this idea of the new building development as a usurper of the natural environment that preceded it. However, whereas Chojnacki associates the place where the Miasteczko was built with (illegal) garbage dumps and incinerators, Bator romanticizes the area as an undeveloped, natural idyll. According to the narrator, the "paskudne miasteczko Wilanów" was created "na miejscu pięknych łąk i pól kapusty."20

Thus, in general, the dominant idea about Miasteczko Wilanów that emerges, both in cultural contexts as well as in right-wing populist media discourse, is that it is a homogeneous, urban enclave in which mostly affluent people from other parts of Poland isolate themselves. At the same time, however, the intrusive nature of the construction project is also addressed. The Miasteczko is not portrayed according to how it was originally conceived, namely as a nature-oriented garden city, but rather as a rape of that very naturalness.

However, the descriptions of the Miasteczko discussed here all remain superficial. The neighborhood serves more as a secondary setting for social debates or as a cliché to clarify the character description of the protagonists. As a result, the portrayal of the district often resembles an abstracting bird's-eye view, in which established prejudices are reproduced without reflection. Only a few productions offer an inside perspective of the district and thus engage with what life there is really like. One such exception is the short film Na Kredyt (2008), which focuses on the experiences of a young couple moving into one of the first completed buildings in Miasteczko. In order to pay the loan for the new apartment, the two protagonists have to work so much that they hardly see each other. They keep in touch through video recordings that they leave for each other in the apartment, but this eventually leads to estrangement from each other, separation, and finally the sale of the apartment. The film shows a less idealized and, above all, a less politicized world of Miasteczko. Rather, it points out how the dream of living the good life in large, modern apartments, which was implanted in the minds young people as a result of the commercialization of the housing market, especially in Poland in the early 2000s, can quickly become a dystopia when paying for that 'good life' leads to it being lost. Indeed, many people who moved to the Miasteczko bought properties they could only afford with 30-year loans and risky repayment rates, and ultimately paid the price for their dream with a significant reduction in their own quality of life.21

The cover of Joanna Bator’s Rekin z parku Yoyogi (2014). https://lubimyczytac.pl/, Free access - no reuse

The cover of Joanna Bator’s Rekin z parku Yoyogi (2014). https://lubimyczytac.pl/, Free access - no reuse

The struggle for a right to city living

Text

But how do the residents themselves experience this narrativization? As far back as 2013, the Gazeta Wyborcza ran a report to gauge the reactions of the residents of Miasteczko to the sweeping attributions and judgements made by people from outside the area.22 The comments clearly show that people do identify with some of the characterizations. However, they also reveal that their motivations for moving to the Miasteczko or buying an apartment, as well as their opinions about life there, diverge from the common assumptions of outsiders. Overall, the prevailing attitude even then was that those projected ideas were artificial and imposed on the residents. One of the interviewees summarizes:

Text

„[…] jesteśmy już zmęczeni dyskusją o lemingach. Człowiek kupił mieszkanie ze względu na cenę, rozkład i widok z okna, a nagle okazuje się, że staliśmy się członkami jakiejś grupy społecznej. Do niedawna żyliśmy tu spokojnie, nieświadomi naszej politycznej roli!“23

Text

Ten years on, you still hear stories like this. In the interviews I conducted with Miasteczko residents in September 2022, most of my interviewees reacted soberly to the question of what kinds of public opinion they found themselves confronted with regarding the Miasteczko and how they dealt with these.24 Adam, 38, a native of Warsaw who has lived in the Miasteczko almost continuously since 2005, believes that the portrayal of the district as a conglomeration of unreflective people is the result of a prevailing tendency in Polish culture to feel envy and resentment toward wealthy people. Ania, 31, who comes from southern Poland and has lived in the Miasteczko for six years, makes a similar statement. In her opinion, the prejudices that still exist are out of touch with reality. Apartments in other parts of Warsaw are now at least as expensive. Many Poles, she continues, will quite arbitrarily search for topics to criticize the prosperity of others because of an underlying social rift. At the same time, however, she speaks about the homogeneity and cohesiveness of the neighborhood: "People here have a similar worldview. This can create the appearance of a closed society, which can be disturbing for others." She herself also has little regular contact with people outside the Miasteczko. This makes the neighborly network there all the more important to her; she believes it is a unique selling point: "We lived a more anonymous life in our old apartment in Kabaty."

Magda, a mother of two older children (11 & 19 years), has been a resident of the Miasteczko since 2019. She sees the neighborly aspect differently. Like Adam, she hardly knows her neighbors. For her, the architectural homogeneity and sense of security that this neighborhood offers is what makes it special. Also, she finds its multiculturalism makes the Miasteczko stand out from other Polish neighborhoods. "When you arrive here, it doesn't seem like a Polish neighborhood. Foreigners feel at home here. And there’s a sense of tolerance, not like in the rest of Poland. It's like a kind of enclave," Magda summarizes. Jan, 39, a German by birth who lived in the Miasteczko for a year, makes a similar observation: "If you compare the population structure of the Miasteczko with that of other European cities, it’s not particularly international, of course. But by Polish standards it is".

In the eyes of its inhabitants, Miasteczko Wilanów is pretty special by Polish standards. Multicultural, tolerant, cosmopolitan. These subjective impressions are difficult to substantiate statistically. Figures from 2017 suggest that the district of Wilanów has the highest proportion of foreigners. However, the Miasteczko represents only a part of this overall district. Drawing conclusions from these general figures about the specific population composition of the residential district is problematic. There are no current statistics that could provide information about the population structure of the Miasteczko. Nor is there any data on the level of satisfaction and living conditions of foreigners living there.

What is clear, however, is that the perception of the neighborhood by its residents is quite positive. According to all the interviewees, Miasteczko Wilanów offers a lot of recreational opportunities – at least for certain age groups. "It's not a dormitory town, it's actually a mini city within a city," says Magda, "which surprised me when we moved here. You can also spend your free time here." For her older daughter, however, this is not the case. There are hardly any facilities for teenagers and young adults. It’s true, there is a lack of parks, skate parks, and clubs. "I am aware that Miasteczko is a good place for young children. But not for older ones," Ania adds.

Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

Text

One of the two public schools in Miasteczko Wilanów on Worobczuka Street.

Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

Text

However, there are many private primary and secondary schools, including the German-Polish Willy-Brandt-Begegnungss...

Text

...and the British Primary School, both on Ledóchowskiej Street.

Text

There are hardly any public schools, and the few that are exist are only elementary level. Even the kindergartens are mostly private. In general, the public infrastructure also leaves a lot to be desired. Public parks, which were included in the original plans, have still not been built, public playgrounds are few and far between, and open green spaces are rare. For this reason, children often use the huge, often empty forecourt of the temple to play soccer, ride bicycles and skateboard. Whether the same children also attend church services with their parents on Sundays in the temple is doubtful. In 2016, not even half of the children living in Miasteczko Wilanów were baptized Catholics.25

In the background, one of the few public playgrounds in the Miasteczko. In front of it the (privately owned) area Plaża Wilanów, which was intended for a park since the time when construction began. Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

In the background, one of the few public playgrounds in the Miasteczko. In front of it the (privately owned) area Plaża Wilanów, which was intended for a park since the time when construction began. Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

The green area around the Temple of Divine Providence was also supposed to be a public park. Instead, the fence surrounding the lawn makes it feel rather bleak and uninviting. Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

The green area around the Temple of Divine Providence was also supposed to be a public park. Instead, the fence surrounding the lawn makes it feel rather bleak and uninviting. Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

Text

Like the professional critics, Adam puts the urban planning failures down to the fact that the planning of the Miasteczko was put into private hands from the very outset: "The project moved further and further away from the original utopian concept basically because there had to be returns on the capital invested. That's where the public sector failed." So, in the actual day-to-day life of the people living in the Miasteczko, the failures of urban planning and urban policy play a greater role than the stereotypes (re)produced by the media and culture.

While at a political and journalistic level the Miasteczko Wilanów is still instrumentalized and discussed as a symbol of the affluent metropolitan community,26 on the municipal level, residents have been actively involved for over ten years in the Stowarzyszenie Mieszkańców Miasteczka Wilanów (SMMW),27 an organization through which they continue to aim to increase the quality of life in their own neighborhood, independently of any party affiliation. This often involves acting as mediators between private investors and the public sector. Through this civic engagement, they have managed to halt the construction of a large shopping center and have made significant inroads towards the construction of public elementary schools. The latter required an agreement between the public sector and investors, as the land for the school had to be acquired by the city from the private investor first. In addition, hundreds of trees have now been planted – most of them by the residents themselves. "Because people want to," says Małgorzata Gabriel, a member of the SMMW, in an interview with Gazeta Wyborcza.28 But probably also because they can afford to finance charitable projects and see them through to completion. After all, "There are no poor people living in the Miasteczko," my interviewee Ania notes. "But that doesn't mean they don't deserve to be here".

The question remains open as to what extent this constantly developing and growing district deserves the (financial) attention of the city.

The Wilanów town hall in Miasteczko Wilanów (Klimczaka Street). Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

The Wilanów town hall in Miasteczko Wilanów (Klimczaka Street). Anna Seidel, Free access - no reuse

Text

At the end of 2021, the district administration protested when the city government drastically cut the budget for the Wilanów district.29 Only recently has construction begun on the streetcar line that has been promised since the Miasteczko was first established and will connect the suburb with the city center. The two existing public elementary schools are bursting at the seams,30 and it was not until early 2022 that the traffic situation was eased by opening a connecting road between the Miasteczko and the adjacent Ursynów district. This raises the question of whether the isolation of the residents proclaimed by the media and in various cultural contexts is being driven by the local people themselves or whether it is based on a reciprocal relationship between external stereotyping and urban planning neglect on the one hand and, on the other hand, the fact that this has resulted in the population becoming isolated and therefore concentrated on and within itself. One thing is for sure, namely, that in this district, people are actively fighting for their rights to a city life, which is probably the only relic of the original idea of Miasteczko Wilanów, which was based on the concepts of New Urbanism and Howard's Garden Cities.