Kharkiv is the second largest city in Ukraine and today had about 1.5 million inhabitants in 2019. The city was founded in 1630 or 1653 in the "Wild Field", as the steppe landscape in what is now southern and eastern Ukraine was called at the time. With the shift of the Russian border to the south, it lost its importance as a fortress, but subsequently became a center of trade and crafts. From 1918 to 1934 Kharkiv was the capital of the Ukrainian Soviet Republic.

Since February 2022 Kharkiv has suffered heavy shelling in the Russian-Ukrainian war.

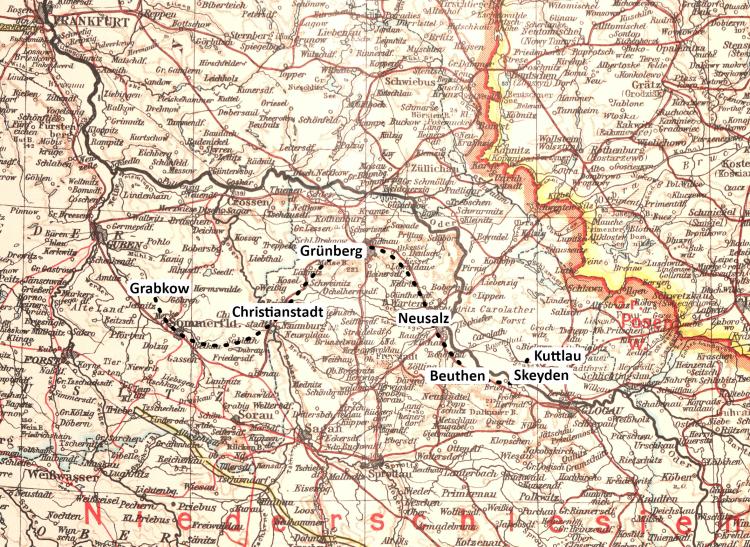

Zielona Góra is a city in the Lubuskie Voivodeship in western Poland. The city is inhabited by almost 140,000 people and is one of the two capitals of the voivodeship. Zielona Góra is situated about 140 km northwest of Wrocław and is part of the northern part of Lower Silesia.

Glogów (Polish Głogów) is a city in western Poland. It is situated in the Lower Silesia Voivodeship (Polish dolnośląskie) and is inhabited by just under 67,000 people. Glogau is situated about 100 km north of the capital of Lower Silesia, Wrocław/Breslau.

The boys made us bridles out of woolen blankets and reins made of a strong cord and we were able to go on. But the Germans told us that there was still war in Głogou [Glogau] and you really could hear shots and explosions. They said that Głogów did not want to surrender, so we could not travel through Głogów. We went to Kotla where we were immediately surrounded by Russians who said that there was a lot to do, that everyone should work, and that we all had to hand in their papers.6

The Russians put the distillery back into operation and the boys worked there. In the evening, everyone came home with a liter of alcohol. That was all their pay. [...] At that time many Poles came to Kotla, so the Russians immediately rounded up everyone to plow and plant potatoes. My fiancé was also plowing, and once the guard who was supervising them didn't like something and he screamed terribly and threatened to shoot him with a pistol. [...] So with a lot of effort and shouting, they somehow managed to plant the potatoes in one big field and in another, and they said they would show us how to work in a collective farm first. Everybody was kind of afraid of these collective farms.8

English translation: William Connor

Map mounting: Laura Gockert

Editing: Christian Lotz