What traces of Russia's imperial claims can be found in Ukrainian, Russian and Belarusian contemporary literature? This article shows that literary texts can point to emerging conflicts much earlier than politics does.

Literature as a predictive model

Text

What can literature actually achieve? Admittedly, it inspires us with its stories and fills our free afternoons and vacation days with its words. It provides little thrills, evokes human and, more recently, animal and plant feelings, and makes its readers cry, laugh and think. Literature ensures stimulating conversations at the table, in the media and in seminar rooms.

The Cassandra team1 attributes another function to literature. Literature can indicate future developments because it can be seen as a source of practical data and information about reality. With this statement, the project would like to advocate for a committed literary studies. The project team shares the opinion that “literary texts (1) refer to key themes and emotions (feelings of threat, freedom / nationalist / separatist feelings) earlier and in a more sophisticated way than other media and (2) influences perceptions and thus the behavior of conflict parties and so on can be actively involved in the (violent) dynamics of a crisis/conflict.”2 In this way, literary texts can be made useful for political and social practice. Through their aesthetic perspective, they are able to maintain a certain distance from the discourses of knowledge, that is, from what is created through language and social practices in different contexts. Crises, wars, trauma, fears and strangeness are phenomena that are discussed in literary texts and played out through characters. 3 Literature deals with these key themes in a more nuanced way than other media by linking these experiences to concrete characters who act in a fictional context.4 Literature is the only medium that, in the best case, tells stories about people without bias and presents them as they really appear in the internal experience of the protagonists. It often tells the “prehistory” of “history” even before there were concrete terms for it, e.g. how Heinrich Mann with his “subject” warned in 1914 of a development that became reality with National Socialism.5

Jürgen Wertheimer, Sorry Cassandra! Warum wir unbelehrbar sind, Tübingen, 2012. Konkursbuch Verlag Claudia Gehrke, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Jürgen Wertheimer, Sorry Cassandra! Warum wir unbelehrbar sind, Tübingen, 2012. Konkursbuch Verlag Claudia Gehrke, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Literature as an archive of social developments

Text

Today, societies no longer suffer from a lack o6 f information but, rather, from an overabundance of facts, data and events. This information and sensory overload makes it difficult to analyze and evaluate situations. In contrast, literature connects phenomena in narrative, creates contexts and provides a holistic picture of the reality depicted. By describing the characters' actions and thoughts, latent tensions, potential for violence and disruptions in systems can be revealed, which can compel people to rethink and change. The disruptions present in the text can be an indication of impending conflicts.7 The Cassandra Project's approach considers literature as an archive and repository of the collective experience of a culture, in which the unspeakable, the mental states of individuals and the mentalities of classes, regions and places manifest themselves in detail.

Cassandra calls

Text

The mythological Cassandra was the daughter of the Trojan King Priam. The god Apollo gave her the gift of prophecy because of her beauty. But when she refused him, he cursed her so that no one would believe her calls. Cassandra always saw disaster coming, but found no one who would listen to her. So she was unable to warn and save Troy from Paris and the Trojan Horse with her exhortations.

The Cassandra team builds on this idea of Cassandra calls in their research. It arises from the conviction that signals can be recognized in the literature that could indicate impending conflicts and possible conflict resolution strategies. For this reason, it is now more important than ever to pay attention to the literature of countries at war or in their immediate vicinity. The war can no longer be averted, but perhaps further escalations can be avoided if the calls of Cassandra are taken seriously. Volker Weidermann admits: “Eastern European writers have been warning us about Putin for years. We read them, celebrated them, and ignored their warnings until it was too late.”8

Conflict societies

Text

Most countries in Eastern Europe, such as Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Ukraine, Poland and Moldova, were members of the

Warsaw Pact

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact, or the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance was a military alliance of the so-called Eastern Bloc under the leadership of the Soviet Union that existed from 1955 to 1991.

until 1990 and are now largely part of the EU, are post-conflict societies. This means that previous conflicts are still present and there is a risk that they may once again break out. In “Secondhand Time” (2013),9

Svetlana Alexievich

Svetlana Alexievich

Svetlana Alexievich was born in Ukraine in 1948 and grew up in Belarus. She works as a reporter and is a writer. Alexievich's works have been translated into more than 30 languages and she has received numerous awards, including: 1998 with the Leipzig Book Prize for European Understanding, the Erich Maria Remarque Peace Prize (Erich-Maria-Remarque-Friedenspreis) by the City of Osnabrück (2001), the National Book Critics Circle Award (2006), the Polish Ryszard Kapuściński Prize (2011), the Angelus Award (The Angelus Central European Literature Award) (2011) and the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade (Friedenspreis des Deutschen Buchhandels) (2013). In 2015 she received the Nobel Prize for Literature.

(Belarus) writes that post-Soviet Russia is still searching for a new identity, even though the Cold War has been over for over twenty years. In

Yuri Andrukhovych

Yuri Andrukhovych

Yuri Andrukhovych was born in 1960 in Ivano-Frankivsk/Western Ukraine, the former Stanislau in Galicia, and studied journalism. He made his debut as a poet and then published essays and novels. Andrukhovych is one of the most famous contemporary Ukrainian authors; his work appears in 20 languages. In 1985 he co-founded the legendary literary performance group Bu-Ba-Bu (Burlesk-Balagan-Buffonada). With his three novels Rekreacij __(1992; english Recreations, Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, 1998), Moscoviada __(1993, English Moscoviad, Spuyten Duyvil Press 2008), Perverzija __(1996; English Perverzion Northwestern, 2005) he has become a classic of contemporary Ukrainian literature. In 2022 he was awarded the Heinrich Heine Prize (Heinrich-Heine-Preis der Stadt Düsseldorf), in 2016 with the Goethe Medal and in 2014 with the Hannah Arendt Prize.

's “Moscoviad”10 (1993), Moscow is described as the “rotten heart of the half-dead empire”.11 The young protagonist gains his identity from the rejection of this city. The countries of the former Soviet Union are politically divided and there are often conflicts within their borders. Some of these countries also have border disputes between themselves that have not yet been fully resolved. There are numerous texts dealing with the disputed region of Eastern Ukraine. One of these works is “The Orphanage”12 by

Serhij Zhadan

Serhij Zhadan

Serhij Zhadan was born in 1974 in the Luhansk region/eastern Ukraine. He studied German and received his doctorate on Ukrainian futurism. Since 1991 he has been one of the defining figures of the young literary scene in Kharkiv. He made his debut at the age of 17 and published twelve volumes of poetry and seven works of prose. For Die Erfindung des Jazz im Donbass he was awarded the Jan Michalski Literature Prize and the Brücke Berlin Prize 2014. The BBC named the work “Book of the Decade”. In 2022 he received the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade (Friedenspreis des Deutschen Buchhandels), also in 2022 the Hannah Arendt Prize for Political Thought and the Freedom Prize of the Frank Schirrmacher Foundation (Frank-Schirrmacher-Preis). In 2018 he was awarded the Leipzig Book Fair Prize. Zhadan lives in Kharkiv, Ukraine.

(2017), which describes how the once familiar environment of Donbass has transformed into an eerie, war-ravaged territory. The book tells about people who maintain their self-assertion and sense of responsibility despite fear, brutalization and destruction.

Sugar Kremlin

Text

Vladimir Sorokin

Vladimir Sorokin

Vladimir Sorokin was born in Bykovo near Moscow in 1955 and is one of the main representatives of Russian postmodernism. After completing his engineering studies at the Gubkin University of Petroleum and Gas in Moscow in 1977, he worked as a graphic artist, book illustrator, painter and conceptual artist, designing more than 50 books. Vladimir Sorokin lives in Moscow and Berlin. He is considered Russia's most important contemporary writer and playwright and a sharp critic of Russia's political elites. His most important novels include __The Serpent 1983, The Obelisk 1992, Bro 2004, Days of the Oprichnik 2006, The Blizzard 2010, Manaraga. Diary of a Master Chef 2018.

― alongside [Ib title=Viktor Pelevin]Viktor Olegowitsch Pelevin was born in Moscow in 1962. He studied electrical engineering and later literature. His first story was published in 1989 and he has been working as a freelance author since 1990. Initially, several of his stories were published in various magazines, and now five novels and around fifty short stories have been published. He is considered one of the most important Russian writers and has long enjoyed cult status, especially among young readers. The New Yorker included him in its list of the “best European storytellers under 35”. He lives in Moscow. In 2001 he received the Richard Schönfeld Prize for literary satire (Richard-Schönfeld-Preis für literarische Satire) from the Hamburg Cultural Foundation.[/IB] and

Viktor Yerofeyev

Viktor Yerofeyev

Viktor Yerofeev was born in Moscow in 1947 into a family of diplomats. He became known for his novel “Russian Beauty” (1989), which has now been translated into 27 languages. Yerofeyev writes regularly for magazines such as the New York Times Book Review; He is also the editor of the first Russian edition of Nabokov. After the Russian attack on Ukraine, he fled to Germany with his family. Important works: Encyclopedia of the Russian Soul 1999, The Good Stalin 2004, Russische Apokalypse 2009, Die Akimuden: Ein nichtmenschlicher Roman 2012, Der große Gopnik 2023.

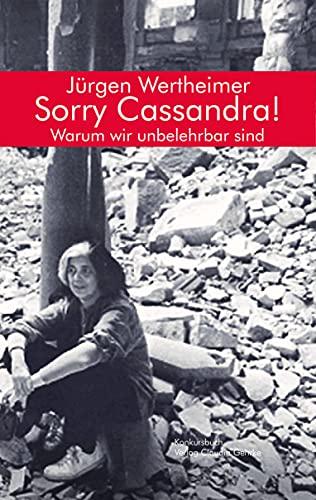

― is considered one of Russia's most famous and respected contemporary writers. In his work “The Sugar Kremlin”13 (2010) he addresses the effect of “sugar-sweet” words. In “The Sugar Kremlin,” Sorokin describes how sweet words and Kremlin figures can be used to spread lies and inconsistencies and distract people from grievances. Vladimir Sorokin's works contain numerous depictions of violence, including rape, cannibalism, mutilation and flogging. Homosexual group sex is also described. These depictions are often carried out as parody, exaggeration or

dystopia

dystopia

Unlike utopia, dystopia creates a negative future scenario.

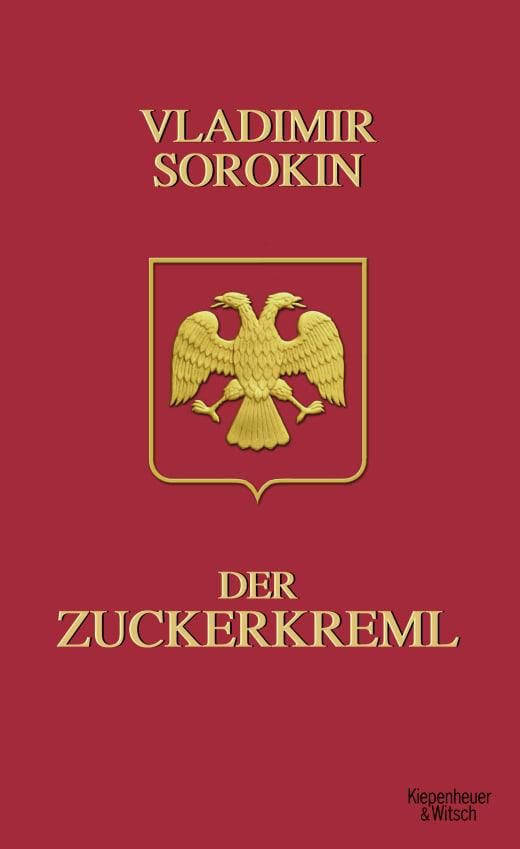

. In view of the current violence in Ukraine, the novel can be seen as a harbinger of things to come. “The Sugar Kremlin” is set in the year 2028. It is the sequel to the novel “Day of the Oprichnik”14 (2006), in which many reviewers wanted to read a deeply pessimistic, Orwellian anti-utopia. In the world of Vladimir Sorokin's novel “Day of the Oprichnik,” Russia in 2027 is ruled by a monarchy that has sealed itself off by a high wall and is held together by religion and violence. In this work, the henchman of power, Komjaga, experiences a day from his life. In 2027, a henchman of power rules, the “Russian bear” is awake and dangerous. In this dystopian world depicted in many of Sorokin's works, violence is omnipresent. Parents beat their children, supervisors abuse workers, and men abuse their wives. The “sugar-sweet Kremlin”, to which everyone has access, holds society together. In these texts, Sorokin sees Russia's situation as hopeless and darker than the world situation of his predecessors from Orwell to Huxley.

In Viktor Yerofeev's “Encyclopedia of the Russian Soul” (2001), a torn Russia is seeking a mythical figure: the Horror, in order to become a great power again. The first-person narrator is an intellectual who, because of a text “about the dawn of a new revelation,” finds himself in the circle of Kremlin secret service agents. With the help of the assistant to former secretaries general, Russia is to be restored as a great power. The figure of horror is portrayed as a kind of Putin, as Yerofeyev writes in the foreword to the novel. The author had already foreseen the current developments in Russia.

Vladimir Sorokin, Der Zuckerkreml, Köln 2010. Kiepenheuer und Witsch Verlag, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Vladimir Sorokin, Der Zuckerkreml, Köln 2010. Kiepenheuer und Witsch Verlag, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Vladimir Sorokin, Der Tag des Opritschniks, Köln 2008, 2022. Kiepenheuer und Witsch Verlag, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Vladimir Sorokin, Der Tag des Opritschniks, Köln 2008, 2022. Kiepenheuer und Witsch Verlag, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Russian debates

Text

In today's Russian society, the 19th century intellectual debates between the Slavophiles and the Westerners are experiencing a revival ("The conflict between Westerners and Slavophiles in 19th century Russia was one of the most important intellectual disputes of that period, which have influenced the philosophical and social theoretical debates of the country to this day. However, the Slavophiles were never a closed group: from Tyutchev to Solzhenycin, many thinkers fought for a strong Slavic entity and a path for Russia that was independent of the West."15 ). On one side there are ultra-nationalists who propagate the idea of Russia going its own way, while on the other side there are those who demand European values and feel at home in western metropolises like as Paris, or in the USA. Victor Pelevin writes in “Tolstoy’s Nightmare” about Putin’s “managed democracy” and the Russian state’s mission to make the lives of its subjects as painful as possible.16

The Belarusian author

Viktor Martinowitsch

Viktor Martinowitsch

Viktor Martinowitsch (also: Victor Martinovich) was born in Belarus in 1977. He studied journalism in Minsk and taught political science at the European Humanistic University in Vilnius. He writes regularly for “Zeit online”. Martinowitsch became known in 2014 with the novel “Paranoia,” which was unofficially banned in Belarus after it was published. In 2012 Martinowitsch received the Maksim Bahdanovich Prize. The novel “Revolution” was most recently published by Voland & Quist.

also describes the seduction of people when the greed for power becomes the strongest motive for their actions in “Revolution”17 (2017). After the novel was published, its publishing house in Minsk was raided, the publisher was briefly imprisoned, and the book was taken off the market without explanation. Martinowitsch writes about human seduction, power, greed ― and a system that has control over the individual. The state apparatus manipulates all areas of social life. It is also a novel about the structures of a patriarchal post-Soviet state that shapes social and political life in Belarus.

Autonomy and exchange

Text

The ambiguity and polysemy that characterize our societies are also often found in literary texts. In addition, it is often clear in the literature that national borders in Europe do not always correspond to regional affiliations. Especially along the dividing line between Russia and Western Europe, there are regions that embody different values and identities than these two large structures. Supporting these regions as a neutral strip could provide relief in conflict situations and build bridges between systems. Andrzej Stasiuk pursues the idea of a bridge between the West and the East in the draft of a unity of the regions that lie south-east of Poland ("The White Raven" (1998), "Galician Stories" (2002), "On the Road to Babadag (2005), “The East” (2015)18). In a double essay “My Europe”19 (2004), Andrzej Stasiuk and Jurij Andruchowytsch write the “most contraversial local history that can be read currently”,20 according to Wolfgang Schneider in the FAZ [Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung]. The authors are not concerned with propagating an anti-Western attitude but, rather, to take a critical view of Western dominance and the associated loss of cultural diversity. The authors emphasize that it is important to preserve and celebrate the history and culture of these regions in order to obtain a complete picture of Europe. They are interested in the abandoned and forgotten regions of Europe between Poland, Romania, the Czech Republic and Ukraine. For them, the cities, rivers, houses and landscapes bear witness to the conflicts that took place in this part of Europe and which were a lesson in despair for the population. They see these regions as a kind of “inter-worldly space” [zwischenweltlichen Raum] that doesn’t really belong to Western Europe or Russia, but has its own identity and history. Overall, the texts by Stasiuk and Andruchowytsch reveal an attitude that opposes the unification and conformity of European culture and identity and instead advocates an appreciation of diversity and local characteristics.

In cultural practice, it is precisely the polyphony, difference and diversity that is the driver and the true moment. Literature proves that preserving diversity in Europe is a way forward.

Transcultural exchange must not only take place in the fields of art and culture ― it must also become the basis of the political agenda in a viable Europe based on heterogeneity. What happens when people think differently is shown in Vladimir Sorokin's “Manaraga”21 (2017): Europe breaks up into small, hostile units: republics, dictatorships, monarchies; and books replace charcoal. The reviewer Daniel Henseler writes: “Sorokin was always good at recognizing trends in the present, projecting them into the future and at the same time accentuating them. In this way, he often recognized developments early on, before they were actually able to take hold. That has to give one something to think about: the fun could become serious.”22

These remarks are only an inadequate compilation of literary texts from Ukraine, Poland, Russia and Belarus. What the texts have in common are the stories about the conflict that plagues the cultures in question, about social contradictions, power fantasies of those in power and the flight into mythology. In this literature, societies are looking for a support, for an overarching goal that they cannot find in the present.

Text

This article is part of a series of articles based on the conference German Narratives on Russia's War in Ukraine. The conference took place as part of the Volkswagen Foundation's War in Ukraine theme week from February 22 to 24, 2023 at Herrenhausen Palace in Hanover. The organizers: Dr. Cornelia Ilbrig (Lower Saxony Academy of Sciences and Humanities in Göttingen), Dr. Jana-Katharina Mende (Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg) and Prof. Dr. Monika Wolting (University of Wrocław). Both the conference and the translation of this article were made possible by the Volkswagen Foundation.

External Image

External Image

External Image

External Image