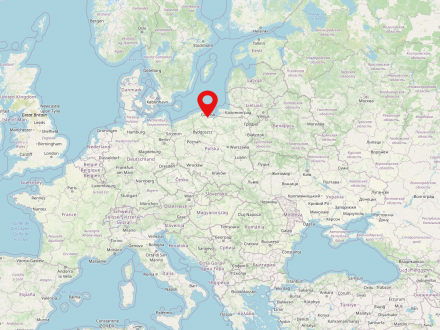

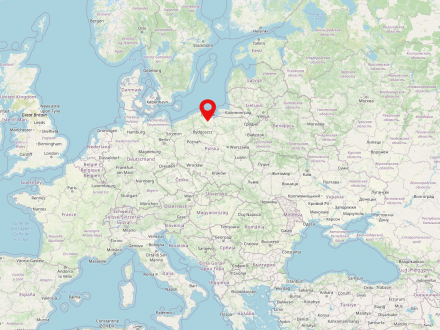

Gdansk is a large city on the Baltic Sea in the Polish Pomeranian Voivodeship (Pomorskie) with about 470,000 inhabitants. It is lying on the Motława River (German: Mottlau) on the Gdansk Bay.

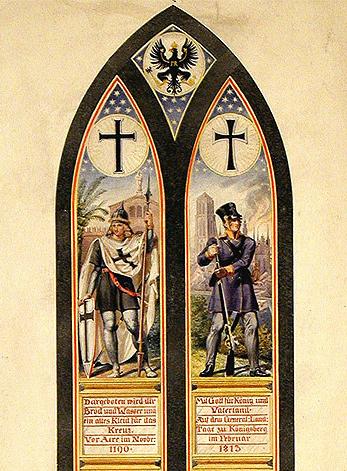

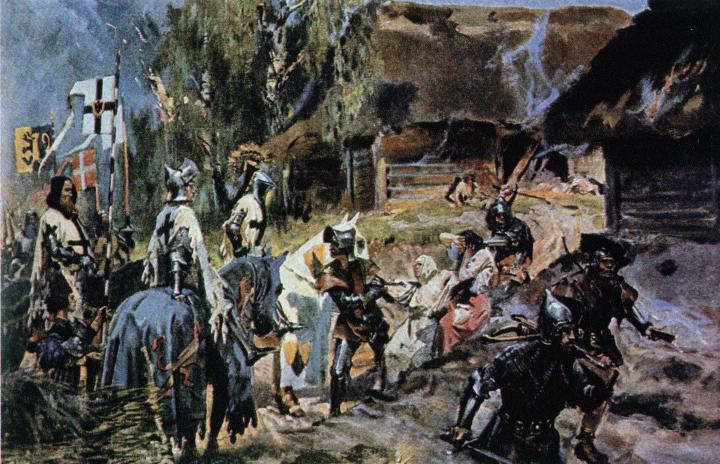

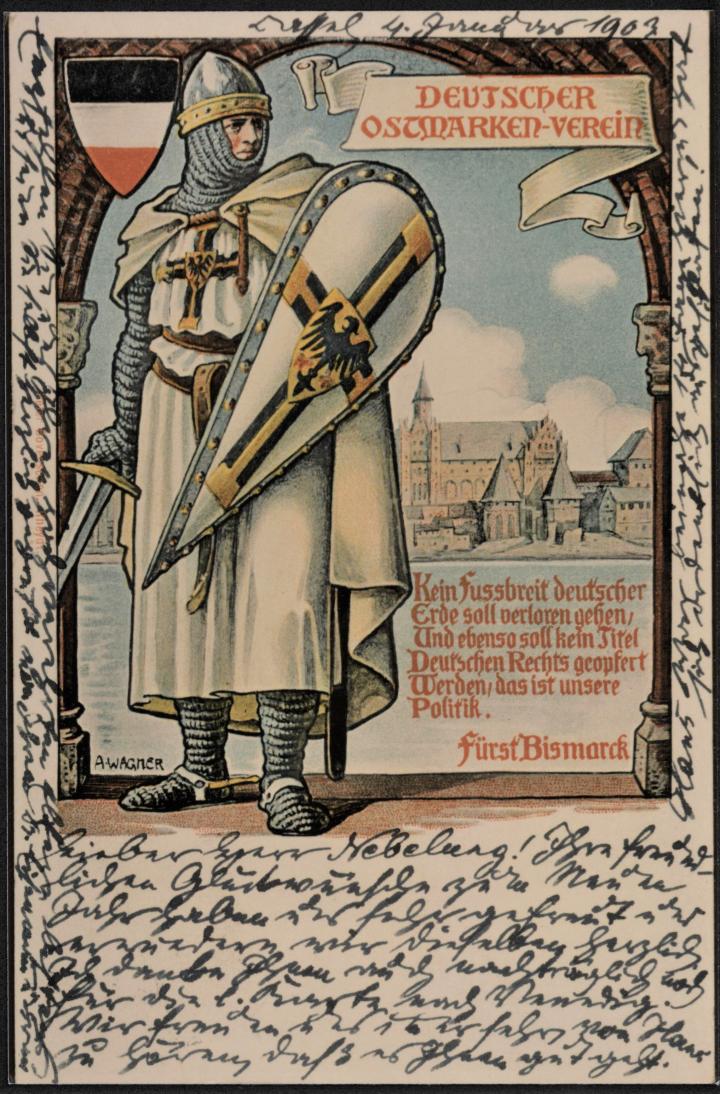

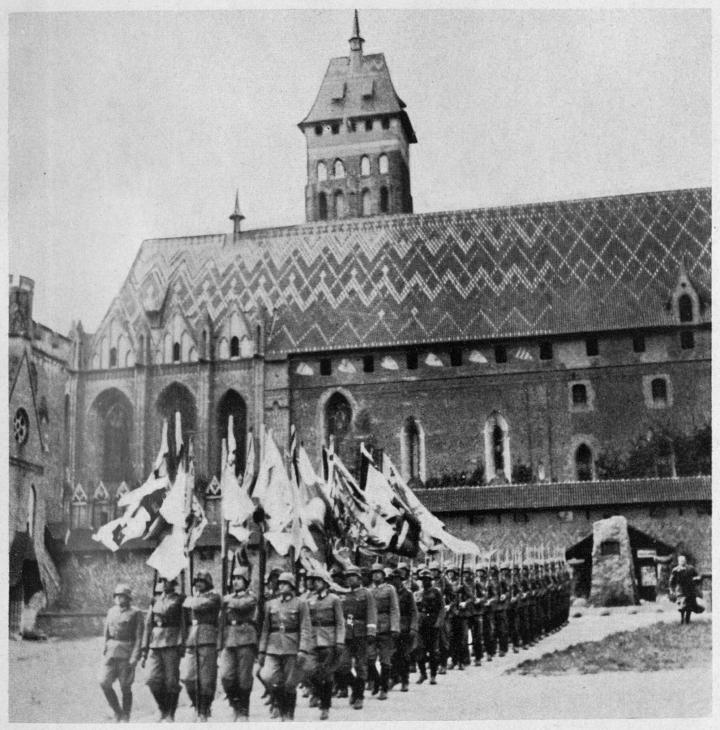

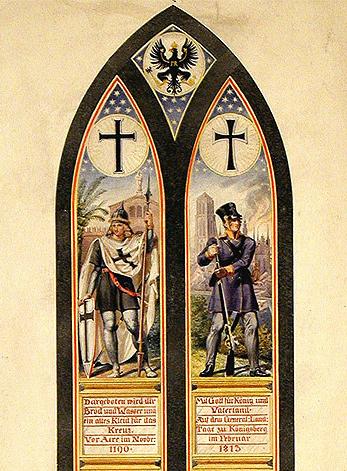

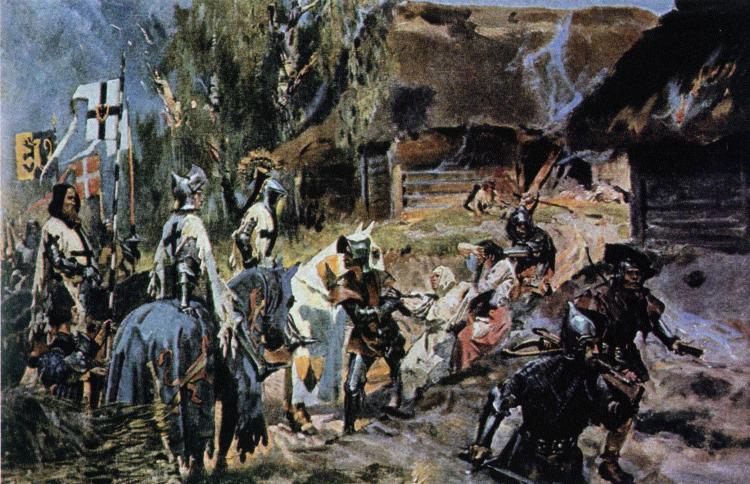

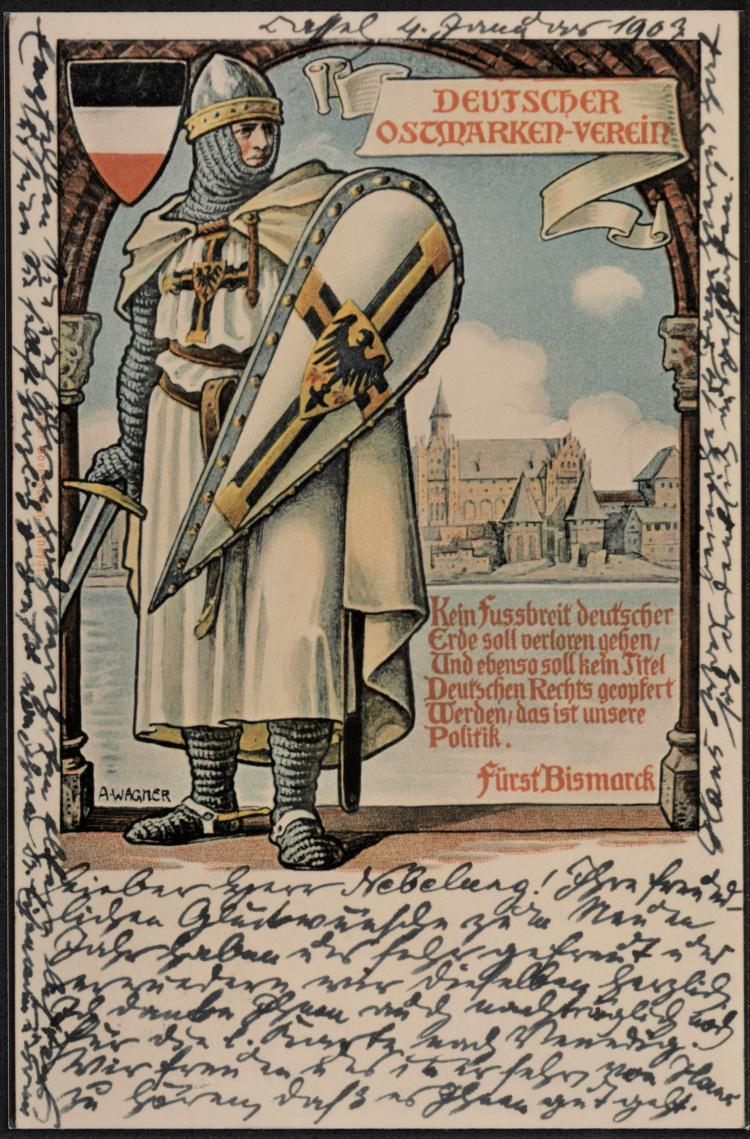

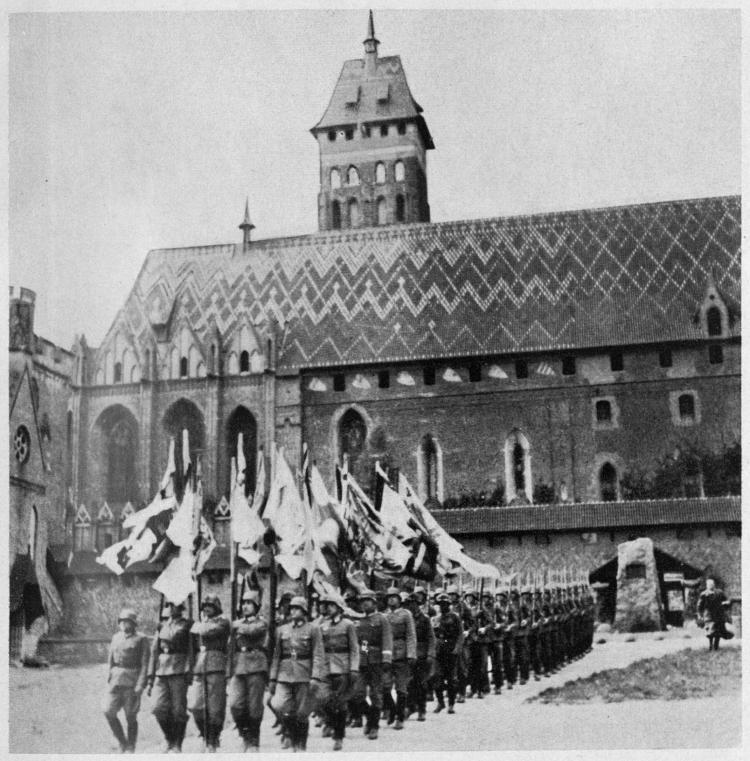

West Prussia is a historical region in present-day northern Poland. The region fell to Prussia as a result of the first partition of Poland-Lithuania in 1772 and received its name from the province of the same name formed by Frederick II in 1775, which also included parts of the historical landscapes of Greater Poland, Pomerania, Pomesania and Kulmerland. The Prussian province lasted in changing borders until the early 20th century. After World War I, parts fell to the Second Polish Republic, founded in 1918. The largest cities in West Prussia include Gdansk (Polish: Gdańsk, today Pomeranian Voivodeship), Elbląg (Polish: Elbląg, today Warmia-Masuria Voivodeship), and Thorn (Polish: Toruń, today Kujawsko-Pomeranian Voivodeship).

As early as 1386, the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were united by a personal union. Poland-Lithuania existed as a multi-ethnic state and a great power in Eastern Europe from 1569 to 1795. In the state, also called Rzeczpospolita, the king was elected by the nobles.

Krakow is the second largest city in Poland and is located in the Lesser Poland Voivodeship in the south of the country. The city on the Vistula River is home to approximately 775,000 people. The city is well known for the Main Market Square with the Cloth Halls and the Wawel castle, which form part of Krakow's Old Town, a UNESO World Heritage Site since 1978. Krakow is home to the oldest university in Poland, the Jagiellonian University.