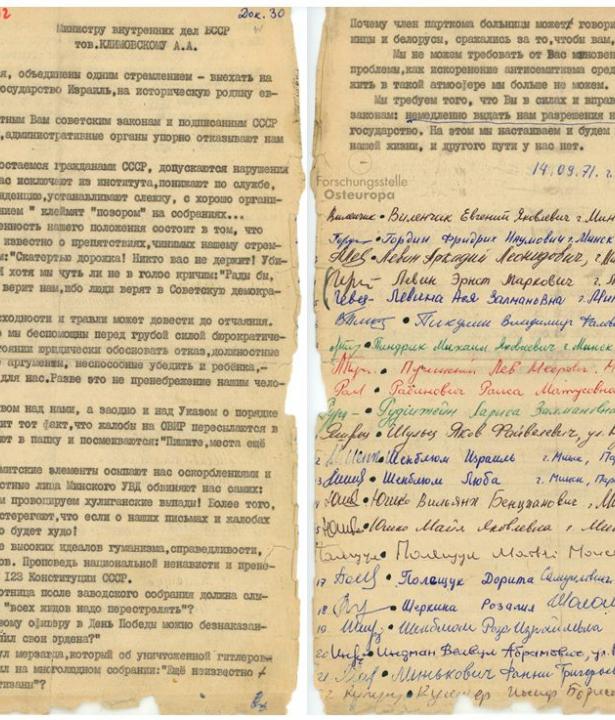

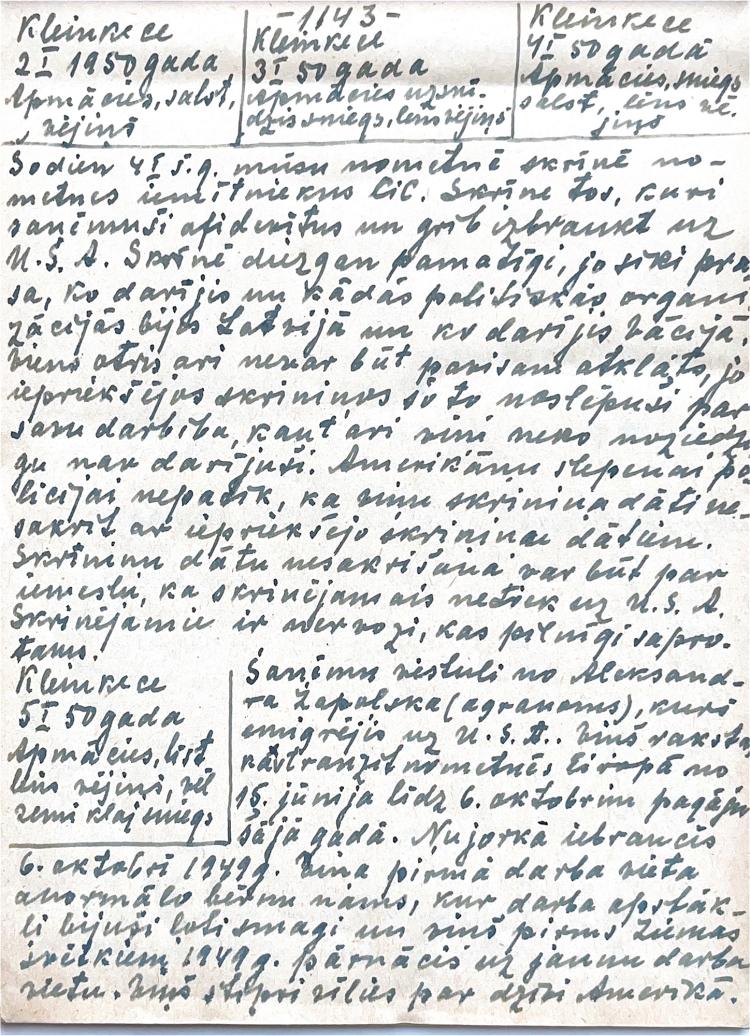

Today, January 4 of this year [1950], the CIC [Counter Intelligence Corps, the US counterintelligence service] is screening the inmates at our camp. Screened are those who have received affidavits and want to leave for the USA. The screening is quite thorough, very detailed questions are asked about what one has done, in which political organizations in Latvia one has been involved, and what one has done in Germany.1

Jelgava is one of ten republic cities in Latvia in the Semgallen (Zemgale) region. The city, which today has about 60,000 inhabitants, is located 44 km southwest of Riga and was the capital of Courland until 1919. As such, it was aristocratic in character and experienced an economic boom in the 17th century, when Kurland even briefly owned colonies in Gambia and Tobago. The city became an important educational center from 1775 with the establishment of Academia Petrina by Duke Peter Biron, whose father had Mitau Castle (lett. Jelgavas pils) built between 1738 and 1772 on the site of the Order Castle built in 1265. This was followed by the establishment of the Curonian Society of Literature and Art in 1815 and the Curonian Provincial Museum in 1818. Today Jelgava is the site of the Agricultural University of Latvia, which has its seat in Mitau Castle.

The picture shows a historical postcard from around 1900, depicted is the Curonian Provincial Museum (Kurzemes Provinces muzejs) in Jelgava/Mitau (Copernico/CC0 1.0).

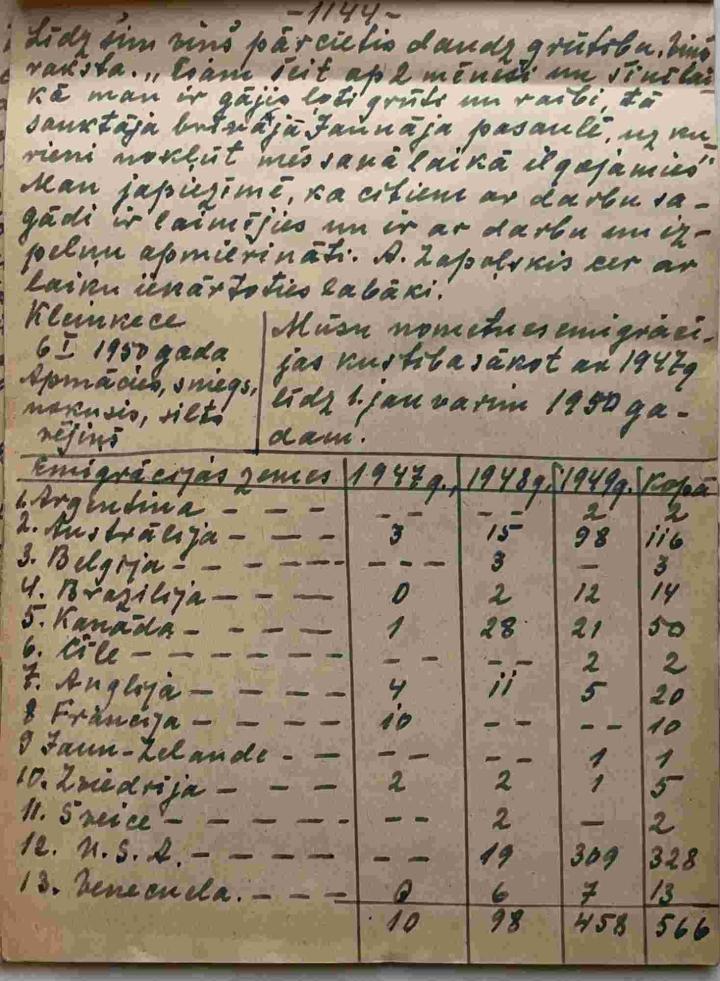

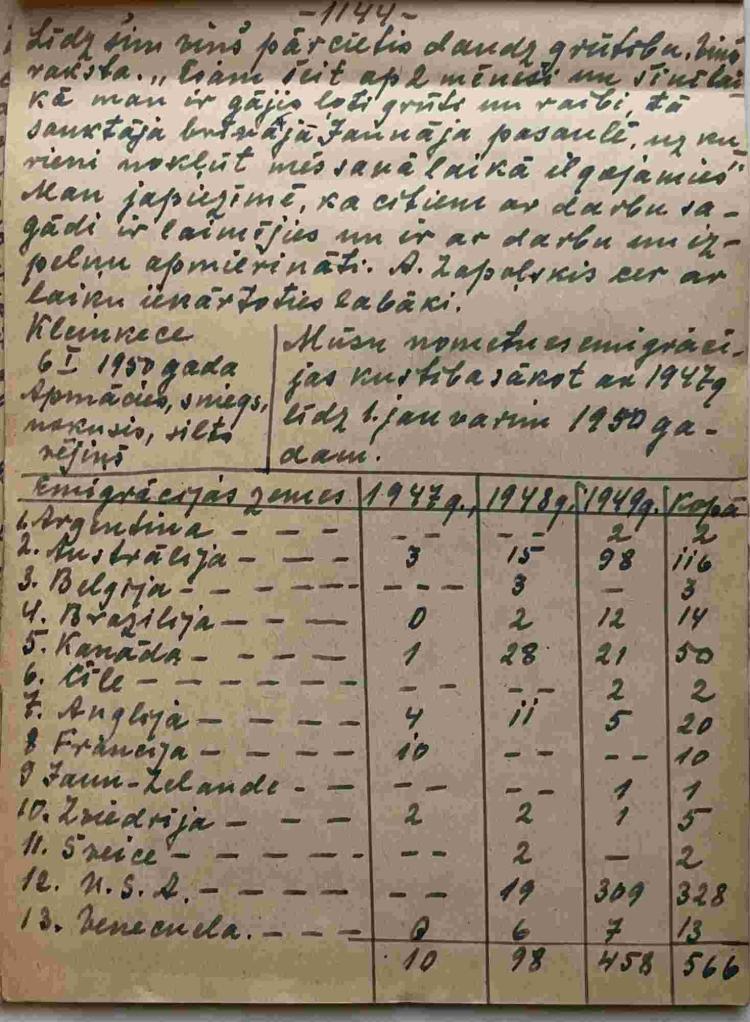

The second largest group (116 persons / families) of those willing to leave the country chose (not always entirely voluntarily) Australia as their new home. The country was willing to accept an unrestricted number of emigrants and enticed them with job opportunities in government services.9

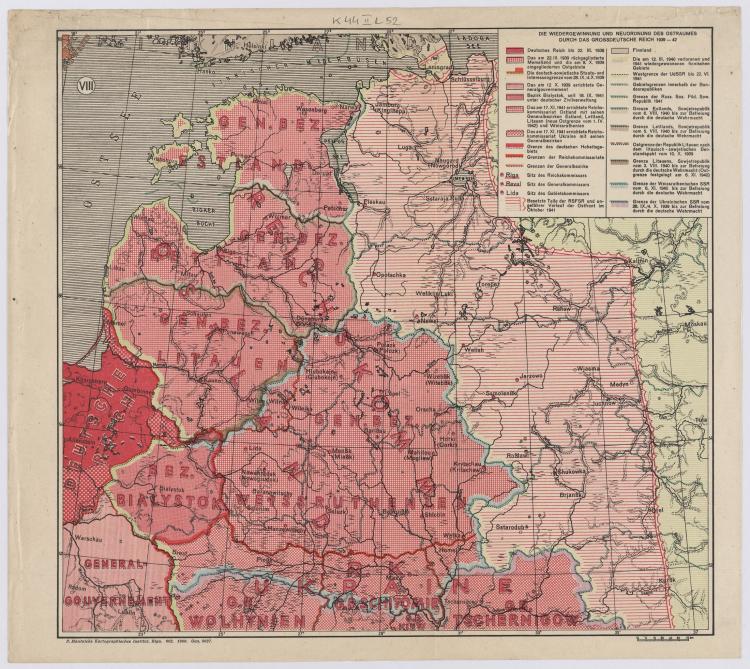

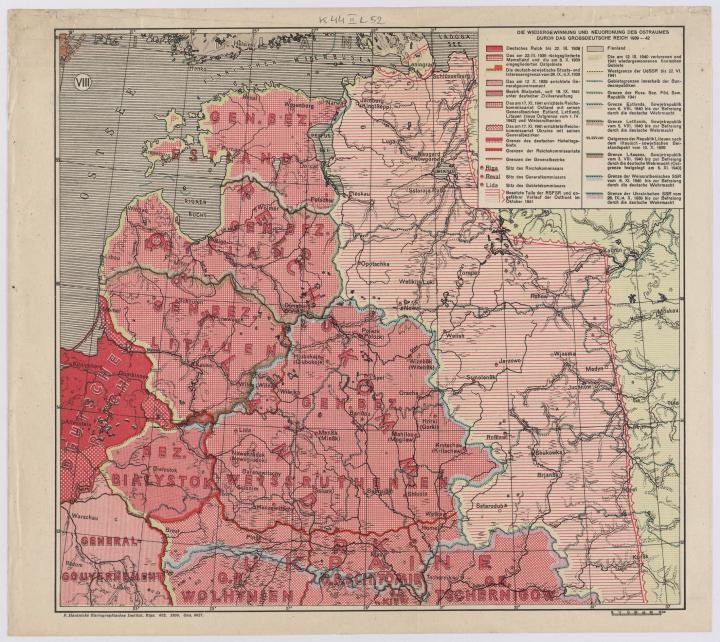

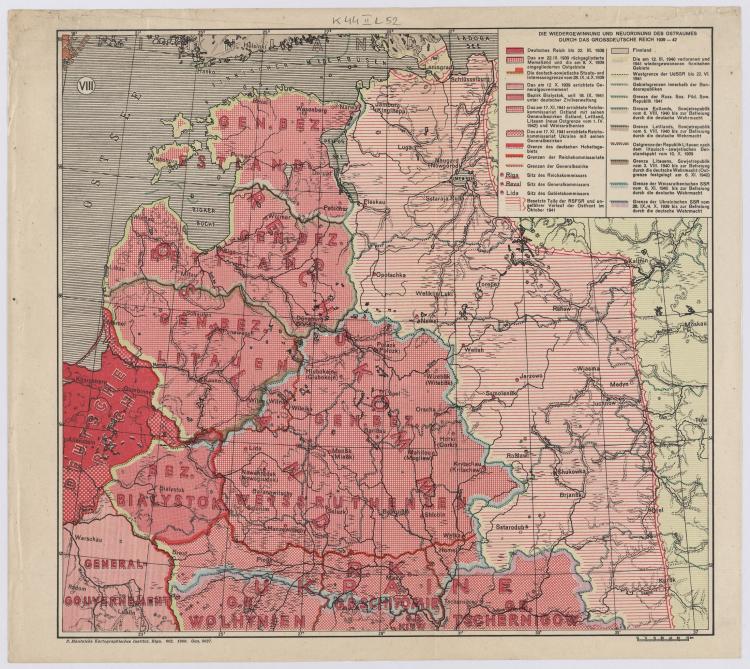

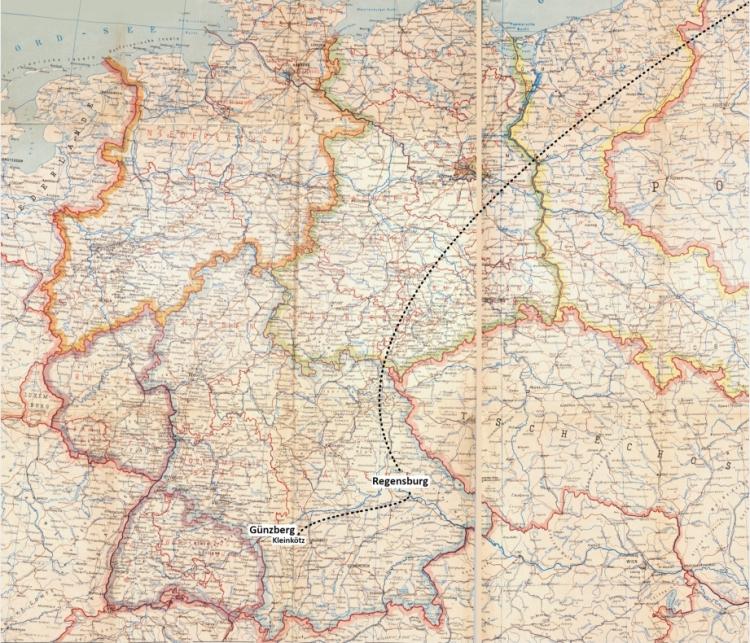

Kartenmaterial des Herder-Instituts

Source selection, analysis, and translations Latvian-German: Agnese Bergholde-Wolf.

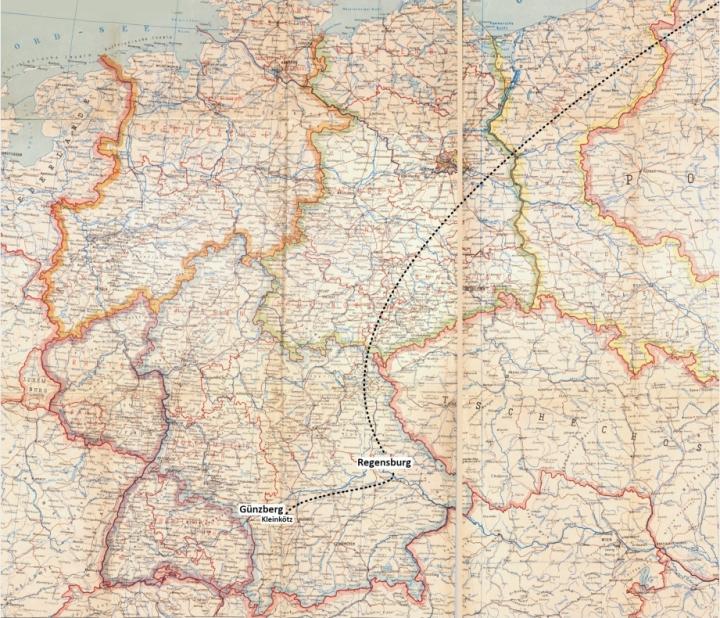

Map montage: Laura Gockert

Editing: Christian Lotz