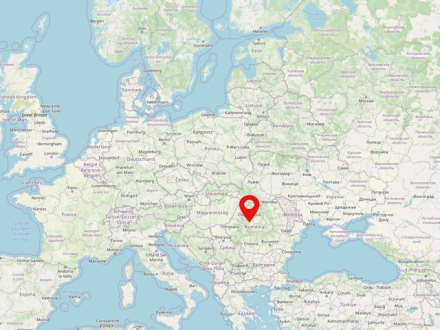

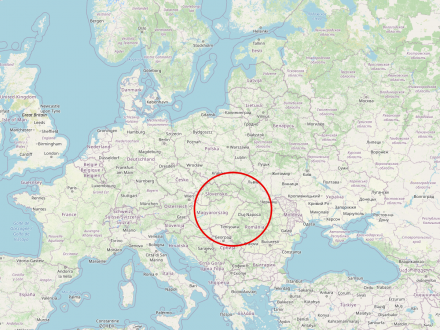

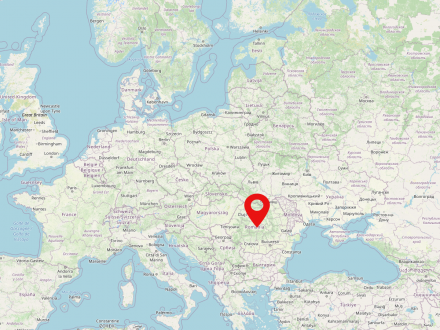

Transylvania is a historical landscape in modern Romania. It is situated in the center of the country and is populated by about 6.8 million people. The major city of Transylvania is Cluj-Napoca. German-speaking minorities used to live in Transylvania.

The Carpathians are european High mountains that enclose the Hungarian lowlands, the so-called Carpathian Arc. It extends to Austria, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Serbia. The main parts of the Carpathian Arc are in Poland, Slovakia, Ukraine and Romania. Geographically the Carpathians have the same origin as the Alps.

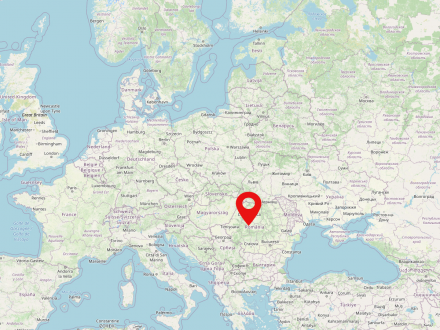

Vienna is the federal capital and the political, cultural and economic center of Austria. Around 1.9 million people live in the city alone, which is one-fifth of the country's population, and as many as one-third of all Austrians live in the metropolitan area. Historically, Vienna is particularly important as the capital and by far the most important residential city of the former Habsburg monarchy.

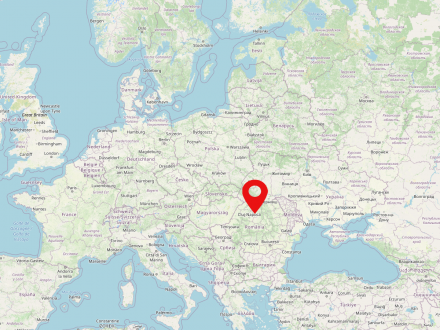

Brașov is located in the historical region of Transylvania in the center of Romania and is a large city with almost 250,000 inhabitants. Brașov was one of the settlement centers of the Transylvanian Saxons.

Şieu (german: Schogen) is a village on the banks of the river of the same name in Transylvania.

Pianu de Jos is a village in Transylvania and belongs to the Pianu commune. It is located on the bank of the river of the same name.

The Secașelor highlands are described by the catchment area of the two Zekesh rivers. It extends in the Romanian counties of Alba and Sibiu. In its centre it is dominated by forests at the edges of pasture and steppe areas.

“Make a poolish1 using 50 g yeast, 1 litre milk, 6 eggs, 180 g butter, a pinch of salt and as much flour as you need […] Knead the resulting yeast dough thoroughly until it starts to form bubbles and separates easily from your hands and from the basin; knock back the dough, sprinkle with flour, and let it rise.

Spread a clean tablecloth over a table, sprinkle it with flour, and flatten the risen dough, starting from the centre and working in all four directions, until it is ½ cm thick […] Then pour over the egg custard (see below) and spread it out so that it covers the dough in a layer as thick as a piece of straw. Draw your forefinger and your middle finger across the egg custard to create lines, dividing the whole into 18–20 cm squares: the dough will be visible along these lines. Using a very hot knife, cut along the lines […] Lift each individual square onto a greased piece of baking paper of the same size (two people will be required for this task, to avoid pulling the hanklich out of shape and so that the custard does not run off) and bake it in the oven. The hanklich squares should be baked in a pre-heated oven for about 10 minutes, until the egg custard is a golden yellow and the underside of the dough is properly cooked but still white.

The egg custard used in the hanklich is a cream made from eggs and fat in equal quantities. For the amount of dough above you will need about 20 medium-sized eggs, 475 g butter, and 500 ml bacon fat. […] Strain the fat and add it to the butter, allowing both to become hot; meanwhile heat the eggs in an earthenware pot, then add the simmering fat, a spoonful at a time, stirring continuously, until the mixture begins to thicken.”

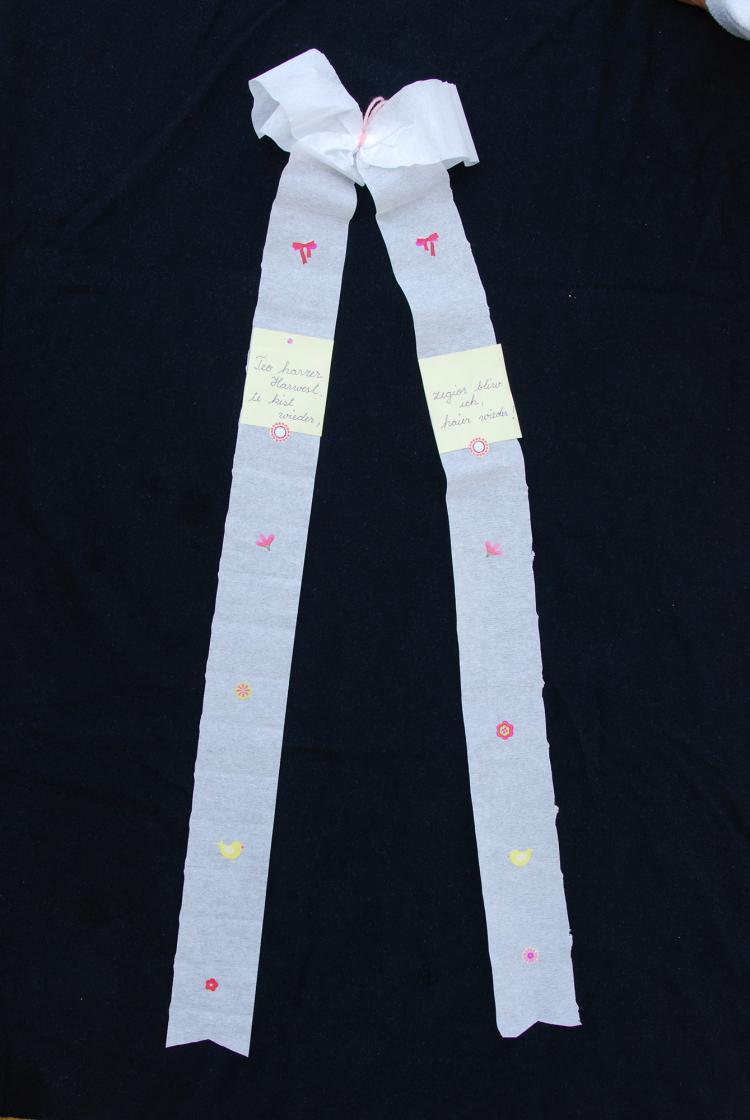

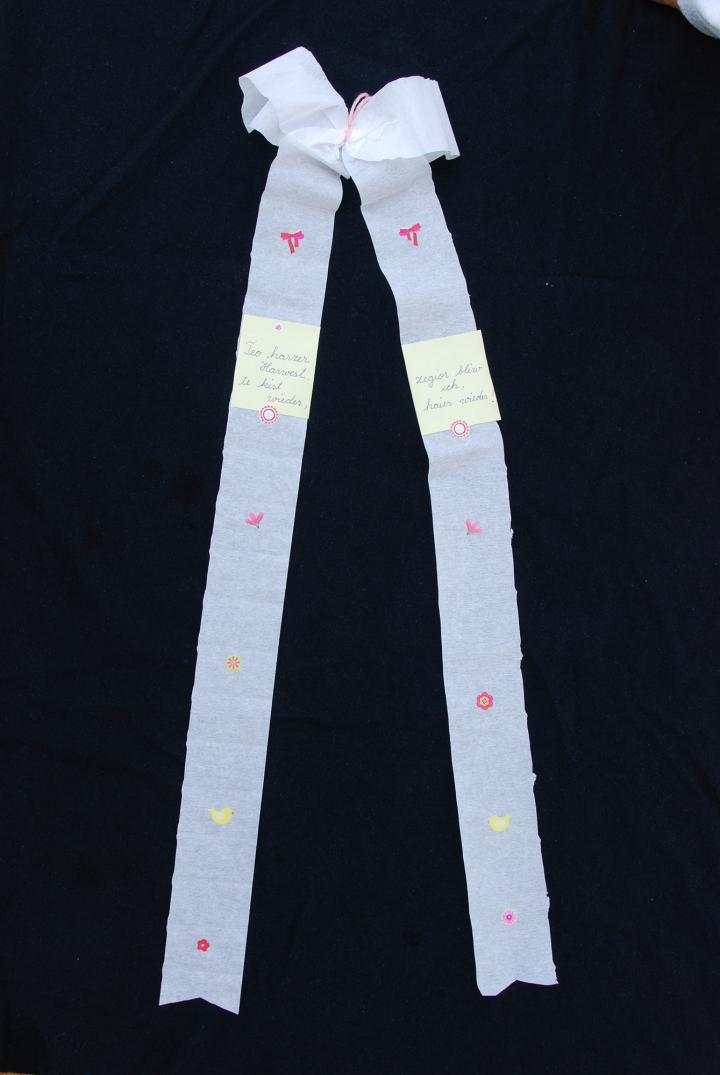

“Folded hanklich” is the ultimate wedding and celebration cake:

“Prepare the dough, as described above, and when it has risen, roll it out on the floured cloth. Brush warm, melted butter onto a square in the middle [of the surface] of the dough, then cut a square out of [another part of] the dough and place it on the original square, brushing the surface with butter again, and continue until the there are about nine sheets of dough stacked on top of each other. Stretch the final sheet out a little so that it covers the sides of the stack. Then lift the folded dough onto a floured board, cover it carefully with a cloth and let it rest in a cool place for an hour. […] This recipe should make about 16–20 pieces.”

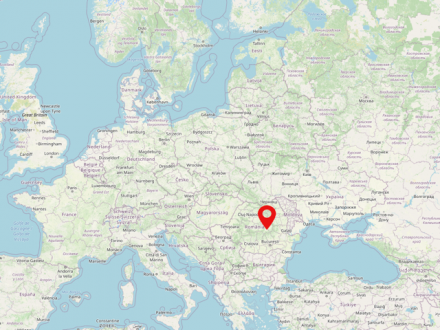

Alțâna (german: Alzen) is a municipality in Romania, first documented in 1291. Alzen is located in Transylvania (historically: "Siebenbürgen") in the Harbach Valley (romanian: Valea Hârtibaciului; german: Harbachtal). Since its foundation, there was a small Jewish population. However, the Jewish cemetery was built over after the last Jewish families left the village.

The Harbach Valley in Transylvania (Romania), also called Haferland, is crossed by the Harbach (Roman. Hârtibaciu), which gives it its name. It is divided into the upper and the lower Harbach valley. In the center lies the town of Agnita (Agnetheln).